Frank,

How would you say mysticism, or even non-discursive contemplation, differ from gnosticism?

Thanks!

— Brian

Frank (attempts) a brief answer:

Gnosticism, mysticism, and contemplation are huge categories, with extensive literature, and varied definitions.

Gnosticism flourished in the ancient Greco-Roman world at the same time as Christianity was emerging. It was not a religion in any organized sense, although there were gnostic conventicles. Many early Christian teachers embraced the gnostic worldview, although not to the extent of teaching the more esoteric myths about origins that some gnostics promoted.

The basic gnostic view was that matter is evil and those who would be spiritual need to transcend the material world. The true God was not the creator god who made the material world; that was the evil demiurge. Gnosis or saving “knowledge,” often received from special revelation, was to attain an awareness of the true God and embrace practices that enabled one to transcend material reality. Gnostics were not comfortable with sacraments or “sacred signs,” although some practiced baptism and observed a communion meal (with water rather than wine). Many embraced an ascetic life that practiced celibacy, although this made them indistinguishable from the many Christians who also embraced celibacy as a Christian calling.

St. Paul the Hermit fed by a raven

Much of what we know about gnostic teachings comes from early church fathers such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Hippolytus who wrote books refuting the heresies. There are some ancient Christian “gospels” (like the gospels of Thomas and Judas) that were rejected for inclusion in the New Testament canon because of their gnostic views, especially that Jesus the Son of God could not suffer the corruption of death.

Since Gnosticism is a worldview rather than a religion, it has never completely disappeared. Some scholars think that American religion is heavily imbued with the gnostic spirit with its individualistic, anti-institutional, anti-authority, anti-historical, anti-sacramental, and anti-environmental biases. See especially Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Resurgence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1992). Bloom regarded himself as a Jewish gnostic. He regarded the Southern Baptists and Mormonism as the archetypal American religions. I can’t help but see the current Republican Party as one large gnostic conventicle. The counter to Gnosticism is a catholic spirituality that emphasizes community, ordered ministries, historical tradition, the care of the earth, and of the body within its incarnational ethos.

Mysticism is even harder to get ahold of. William Ralph Inge, in Christian Mysticism, listed no fewer than 26 definitions or descriptions of mysticism or mystical theology. It comes from the Greek mystikos, which means “hidden” or “secret.” The term mysterion is used in the New Testament, especially by St. Paul in Ephesians and Colossians, to refer to the secrets of God that were hidden for ages now revealed in Christ. The Greek Church called mysteria what the Latin Church called sacramenta.

Mysticism can be generally regarded as seeking an experience of God’s presence. God’s presence can be discerned in nature, in Scripture, in sacraments, in one’s daily life and work, sometimes even in other people (saints). In this sense, mysticism need not be gnostic, although gnostics could be mystics. Mysticism is a spiritual approach to life but does not project a particular worldview. Great teachers of mystical theology in Christian history include the ancient desert fathers (see the icon above this article) and many medieval women such as Hildegard of Bingen, Mechtild of Magdeburg, and Julian of Norwich.

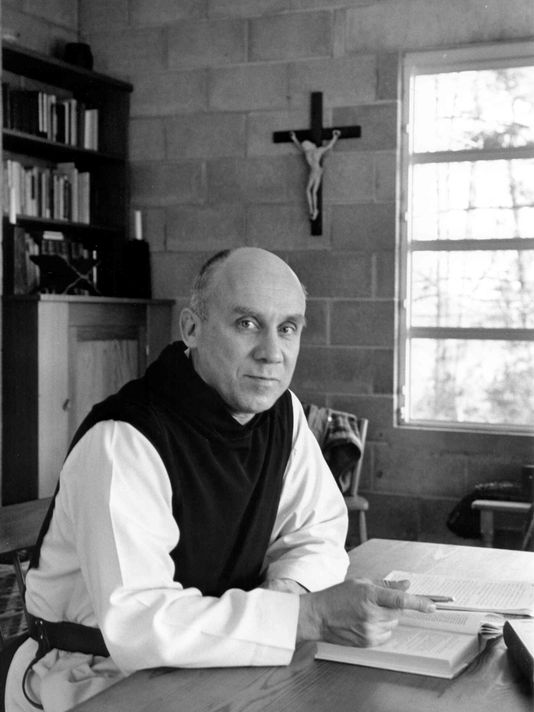

The Trappist monk, Thomas Merton of Gethsemane Abbey, wrote that “To reach a true awareness of [God] as well as of ourselves, we have to renounce our selfish and limited self and enter into a whole new kind of existence, discovering an inner center of motivation and love which makes us see ourselves and everything else in an entirely new state.”

Thomas Merton, Monk of Gethsemane Abbey

Merton would have counseled that one can reach this true awareness of God and self through contemplative prayer. Our questioner mentioned “non-discursive contemplation,” which refers to silence. Contemplation is less an intellectual than an intuitive pursuit. Realizing the love of God for oneself and for the whole world is one of the intuitive insights of mystics. Contemplatives search among the simple and ordinary things to discern God’s love. Once again, therefore, silent contemplation is not necessarily gnostic, although some gnostics may engage in it.

An excellent little introduction is Thomas Merton’s Contemplative Prayer (New York: Doubleday Image Books, 1971). Contemplative prayer is not opposed to liturgical prayer. In fact, the two flourish side by side in monasteries. Nor is contemplation opposed to action. The Franciscans have been examples of this fusion. Franciscan Father Richard Rohr named his center in New Mexico the Center for Action and Contemplation. Contemplation leads to and renews activism, as many social reformers discovered. Contemplation can also be practiced by ordinary people, not just by monks and religious and social activists. What we look for and find in God we must also look for and find in the world. If we find God to be a God of justice, we must also look for justice in the world, because justice is of God.

Toward the end of his life (cut short by an automobile accident in Tibet), Merton was in dialogue with Buddhist monks and had been visiting Buddhist monasteries. There has been much influence from Buddhism on revitalized Christian interests in meditation, such as the practice of mindfulness. I began a more regular practice of meditation after I began to practice yoga. I learned how to use the breath to calm my body and then my mind. Often when we come to meditation from the affairs of the day our minds are agitated (what Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras called the “turnings of thought”—citta-vrtti). I learned that if my mind wandered (which it always does) I can always return to the breath and use my breathing to refocus. One can meditate just on the breath, which leads one to contemplate the gift of life itself and the One who is the author and giver of life.

Our questioner didn’t ask about meditation, but I’m going to discuss it anyway, because it is the condition that makes contemplation possible. The benefits of meditation depend on what we are looking to get out of it. For some it may be just an opportunity to become more centered, to remove anxiety, and to bring serenity into our lives. For the Christian, God should be a part of our meditation since God should be a part of our lives. That is, we live with a God-consciousness.

It’s nice to have a time and place for meditation. Unfortunately, it’s seldom in church before or after worship because there’s too much distraction caused by the presence of people and the activities going on in the building. Not many church buildings are open during the day on weekdays so that people can just wander in and sit (although some make meditation chapels available). Some yoga teachers allow for a few moments of meditation at the end of a yoga class, although these periods aren’t long enough to get into real meditation. A retreat also affords an opportunity to withdraw from the world and one’s regular activities, so that one may return to the world and to one’s responsibilities refreshed in body, mind, and spirit.

But in reality, many of us have moments in our everyday lives when we can develop a deeper awareness of ourselves in relation to God and to the world around us. Maybe meditation is practiced when taking a walk on a beach and watching the waves wash in; or hiking through a forest or field and noticing the breeze moving the branches of the trees or the blades of grass or strolling through a city park and noticing the activities of people who are enjoying being outside. (There can be a walking meditation as well as a sitting meditation. See Frank Answers About Walking Meditation) These can be opportunities to experience great clarity, stillness, and the contentment of being in the moment, without the regrets of the past or the expectations of the future.

The advantage of a formal meditation practice is that it brings discipline, regularity, and depth to meditation. By having a regular practice, by working within a tried-and-true structure, and by investigating our feelings and thought processes in a systematic way, there is the possibility of achieving calmness and focus and coming to some conclusions—or none at all. (Meditation can be a time to empty the mind’s inbox.) The best time and place for a sustained practice may be in one’s own home in the early morning. In the summer months it might also be possible to sit in a secluded place outdoors to contemplate how we relate to the world around us.

Pastor Frank Senn