I originally posted this on Earth Day in 2020 during the pandemic when so many people around the world were quaranteening and the Earth’s atmosphere seemed cleaner because there was less traffic, less travel, less carbon emissions. Earth Day can be used as a time for political action, promoting clean energy, cleaning up the environment (land and water). maintaining and planting trees. It can also be used as an encouragement to immerse ourselves in the natural world as a way of connecting with it. That’s what the Green Man and his friends represent: the connection between humanity and nature.

Question: Celtic folklore seems to have become important in the environmental movement. For example, the Green Man head has become a symbol of the movement. Do you know what there is in the Celtic tradition that would connect it so strongly with nature?

Answer: Yes, the Green Man has become a symbol of the environmental movement. The Green Man might be located in ancient fertility rites. But the Green Man has been popularized as a symbol of the environmental movement.

I think many people have become disenchanted with the modern technological pollution of the environment, so it’s not surprising that we become re-enchanted with the natural world as a reaction. In traditional fairy tales, enchantment can refer to a magical spell, a charm, or bewitchment. Enchantment also refers to the sense of wonder or delight. Certainly a sense of wonder and delight in the natural world is communicated in folklore. The Celtic culture was very attuned to nature, and it is a culture that is close to the U.S., considering all the Celtic settlers in early America (Scots, Irish, Welsh, some Britons (people with roots in western France).

The northern forests evoked a sense of enchantment. It could be the habitat of figures from medieval folklore, including the green man, wood sprites, Sheela na gig, and the Celtic forest god Cernunnos. While some of these figures are common throughout Europe, they are most associated with the Celtic lands of Gaul, Great Britain and Ireland.

It is from these areas in particular that the folklore explored in this article comes. The Celtic people had an intimate relationship to nature. This is not to say that other peoples didn’t or don’t have a strong bond with nature. Many indigenous people around the world feel a connection to nature that modern Western people lack. The Green Man, as we’ve come to know him, was a part of Celtic folklore. The vegetable man, whose face appears in stone on many medieval church buildings in Europe, such as the Cathedral of Derby, UK, is believed to be the spirit of nature, or, more particularly, the spirit of vegetation.

The idea of the Green Man comes from representations throughout history that show a man’s face covered in foliage with vegetation coming out of his ears, nose, and mouth. Some scholars believe that the original “Green Man” was the Greek god Dionysius (Roman: Bacchus), the god of wine and festivity, who was always portrayed with a wreath of grape leaves on his head, a bunch of grapes nearby, and a cup of wine in his hand. Roman influences are found in Gaul and Britain from the time of late antiquity when these lands were part of the Roman Empire.

The very concept of a green man who is a part of nature is a fitting symbol for the Gaia idea that humans are part of the Earth, not separate from it. Our ancestors saw in green men and wood sprites a human connection with the natural world. Whatever meaning the spirit of vegetation had in pre-Christian folklore, his face was ubiquitously carved in stone on church arches and columns in the Western Middle Ages.

In spite of these faces on medieval churches, the name “Green Man” is actually an invention of the 20th century. Julia Somerset, wife of Major Fitzroy Richard Somerset, fourth Baron Raglan, who was noted for his independent scholarship and writings on folklore topics, also investigated the mythic-ritualistic origins of underlying popular culture. Lady Raglan wrote only one article on a folklore topic and it’s what she became famous for. She was interested in the persistence of this vegetable-human figure on church walls throughout Europe and set out to study its origins. Her single article appeared in the journal Folklore, and it almost certainly has had a more lasting influence than anything else written by her or her husband. No name existed for this figure until Lady Raglan gave him a name in this article: the Green Man. The name stuck.

Figures of the Green Man on church buildings would seem to be a blending of Christianity and paganism. Roman liturgical forms replaced the original Celtic Latin rites. But the piety of the Celtic people was deeply rooted in nature. This can be seen in the famous Lorica attributed to St. Patrick (ca. 389–461). The hymn is both solidly Trinitarian and also celebrates God’s presence in nature.

The Lorica of St. Patrick (The Deer`s Cry)

I arise to-day:

vast might, invocation of the Trinity,—

belief in a Threeness

confession of Oneness

meeting in the Creator. . . .

I arise to-day:

might of Heaven

brightness of Sun

whiteness of Snow

splendour of Fire

speed of Light

swiftness of Wind

depth of Sea

stability of Earth

firmness of Rock.

I arise to-day:

Might of God for my piloting

Wisdom of God for my guidance

Eye of God for my foresight

Ear of God for my hearing

Word of God for my utterance

Hand of God for my guardianship

Path of God for my precedence

Shield of God for my protection

Host of God for my salvation . . .

Christ with me, Christ before me,

Christ behind me, Christ in me,

Christ under me, Christ over me,

Christ to right of me, Christ to left of me,

Christ in lying down, Christ in sitting, Christ in rising up

Christ in the heart of every person, who may think of me!

Christ in the mouth of every one, who may speak to me!

Christ in every eye, which may look on me!

Christ in every ear, which may hear me!

I arise to-day:

vast might, invocation of the Trinity

belief in a Threeness

confession of Oneness

meeting in the Creator.

Perhaps the retention of this figure from pre-Christian paganism was a way of affirming the goodness of God’s creation. In the springtime especially, the church prayed for the blessings of the seedtime in rogation processions through the fields and continued to support fall harvest festivals. Irish hymns like St. Patrick’s Lorica (also called St. Patrick’s Breastplate) evoke nature. One of the stanzas of the hymn is paraphrased by Cecil Alexander thus:

“I bind unto myself today

The virtues of the starlit heaven,

The glorious sun’s life-giving ray,

The whiteness of the moon at even

The flashing of the lightning free,

The whirling wind’s tempestuous shocks

The stable earth, the deep salt sea,

Around the old eternal rocks.”

This was a culture attuned to its natural surroundings. It’s is a culture in which the Green Man flourished and had his vegetable head carved on stone churches.

There is hardly any medieval church building that lacks Green Man faces. Chartres Cathedral in France (completed in 1220), widely considered one of the masterpieces of Western architecture, features up to 70 green men in a whole variety of different forms, including leaf masks, disgorgers of vegetation, and human facial features in the midst of plants. Located in Western France, Chartres would have been an area with Celtic cultural influence.

The medieval gothic cathedrals had the appearance of a forest on their interior because of tall columns, vaulted ceilings, and natural light coming in through colorful stained glass windows between the arches. It’s not surprising that these gothic architectural wonders were built in areas with plentiful forests with tall trees.

While the Green Man earned his name because of the green foliage of spring, Lady Raglan didn’t take into account that there were also figures of this nature man with fall foliage, suggesting that he is a symbol of death and decay as well as well as new life and fruition. The Green Man, as we have come to regard him, is a symbol of the cyclical rebirth of nature in the coming of spring with its fresh green foliage. So, on Earth Day we should recognize and celebrate the renewal of nature that the Green Man personifies and as we anticipate the full bloom of summer.

As the spirit of nature ,the face of the Green Man has been carved into trees as well as stone, although those carvings don’t last as long as stone sculptures. But wood is easy to work with and there is a variety of Green Man tree carvings.

Green men sculpted in stone and trees inspired the creation of bronze sculptures (which will turn green as they weather) of green men placed in outdoor gardens.

As the figure of the Green Man became more known, photographers became interested in living artistic photographic portrayals of the Green Man surrounded by foliage and entwined with leaves and vines.

Completely naked green men and green boy sculptures with their penises showing have been placed in gardens. The Green Man is also a symbol of fertility.

The following naked green boy photographed in the bushes has attained a little more physical maturity than the above green boy statue.

Sheela na gigs.

Sheela na gigs is also a carving found on medieval churches all over Europe. She is naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. Scholars disagree about the origins and purpose of these grotesque figures. It is most commonly believed that Sheela was a pre-Christian fertility goddess, which would explain the extended and welcoming vulva.

An article on Sheela na gig in Mircea Eliade’s 16-volume The Encyclopedia of Religion (1993) draws parallels between Sheela and the ancient Irish myth of the goddess who granted kingship. She would appear as a lustful hag, and most men would refuse her advances. But the one man who slept with her found her transformed into a beautiful maiden who conferred royalty on him and blessed his reign.

Cernunnos

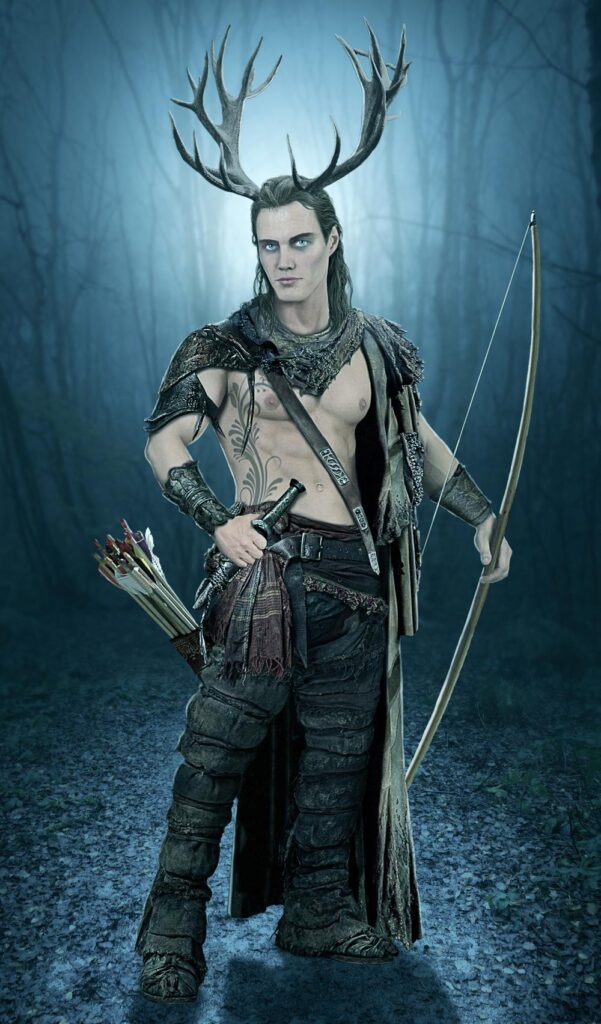

A variant of the Green Man in Celtic mythology is the god Cernunnos. The basis of his name (and even its spelling) and his exact mythology is lost in the mists of pre-history. He is viewed as a god of vegetation like the Green Man, but also of animals. With his mighty antlers he is the Lord of the forest and of wild things. He relates especially to male animals, such as the stag in rut. Here Cernunnos is surrounded by animals such as a falcon, snake, and deer.

Cernunnos is also clearly a Celtic deity, as this figurine shows by having the god hold up the torc that Celtic warriors wore around their necks. Cernunnos embodies animal features such as the ears and hooved feet.

His antlers put him in the category of horned gods, and his sexual prowess suggests that the Greek and Roman god Pan (portrayed as a satyr — half man and half beast with an enlarged penis) could be a relative in that culture.

This metal etching on the on the first century B.C. Gundestrup Cauldron found in Jutland, now on display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, shows features of the Cernunnos mythology. He has antlers and holds in his right hand the Celtic torc, a symbol of nobility. In his left hand is the serpent who guards the treasure of the earth. He is surrounded by forest animals — a stag to his right with identical antlers, a wolf and lion to his upper left, rams butting each other in the lower right, a boy on a dolphin, and two bulls in the upper corners.

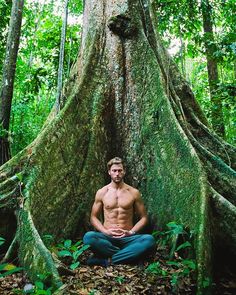

It’s interesting that Cernunnos is sitting in a lotus position, perhaps reflecting the Indian origins of the Celtic race. Yoga has also had its naturist advocates who enjoy doing yoga poses outdoors in natural areas. Many of the yoga poses are named after plants (tree, lotus) and animals (cobra, pigeon).

Stags and the hornless deer were important cult creatures for the Celtic people. The stag was admired for its grace, speed and sexual prowess during the rutting season. Because of the stag’s association with sexual prowess, phallic amulets were made and worn by those wishing to be imbued with that animal’s sexual power.

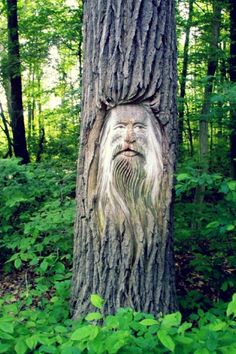

Celtic warriors were known to mentor young men as hunters and warriors and even to sleep with them. Cernunnos is known for his bi-directionality. He relates to both animals and humans, and perhaps also to both male and female sexes. Edward C. Sellner, The Double: Male Eros, Friendships, and Mentoring: From Gilgamesh to Kerouac (Maple Shade, NJ: Lethe Press, 2013), writes: “Contrary to the religious formation many of us have received which made us wary of anything related to sexuality, certain of our friendship, including male [i.e. same-sex} friendships, will have an erotic quality to them—as the ancient Celts realized. They were grateful for this life-giving energy, expressed in their pagan devotion to Cernunnos, the archetype of sensuality and the instinctual world. As that powerful archetype, Cernunnos can be found in all of us: in our desire at times to shed clothes and be naked in the rich presence of nature, to be one with the landscape; to be naked, like our first parents who walked the earth; naked as when we were first born; naked as when we had our first sexual intimacies.”

Sellner continues: “The ancient Celts did not limit the erotic to the human body alone. Their eros included the beautiful landscape in which they lived which caused them to be filled with wonder and awe at its mysterious beauty and power. They believed that the rivers and trees had a melodious voice and that one could hear music in the moving waters and rustling leaves. The positive side of their erotic traditions included a profound appreciation of physicality, of natural beauty – whether in nature or in the feminine and masculine expression of beautiful bodies. Above all, their sexuality was perceived as a sacred phenomenon, including even when Celtic men expressed themselves with one another as bed-partners or simply as friends” (p. 101).

In the natural world same-sex relationships are not uncommon among animal species and humans. Same-sex behavior has been studied by modern biologists and anthropologists, but it was definitely practiced by ancient people like the Celts who were more attuned to nature than we are. To such ancient peoples homosexual behavior would not have been regarded as “contrary to nature.” What was “contrary to nature” to Romans was Celtic adult men’s egalitarian approach to sex by taking both active and passive roles. Adult men taking the passive or receiving role would have been taboo for the aggressive Romans.

Cernunnos is known for his bi-directionality. He relates to both animals and humans, and perhaps also to both male and female sexes. Sellner writes: “Contrary to the religious formation many of us have received which made us wary of anything related to sexuality, certain of our friendship, including male [i.e., same-sex] friendships, will have an erotic quality to them—as the ancient Celts realized. They were grateful for this life-giving energy, expressed in their pagan devotion to Cernunnos, the archetype of sensuality and the instinctual world.

With this historical background it’s not surprising that gay men have been attracted to Cernunnos as a model by which to address serious issues of mental health, depression, and suicide among gay men in the U.K., as well as toxic masculinity among straight men. Men’s organizations have encouraged men to return to the outdoors and to cleanse their minds and souls in nature. Experiencing the natural world in the natural state, without the enclothment of human culture and its social expectations, aids in connecting with the natural environment.

Cernunnos made quite a different comeback in the early 20th century with the emergence of neo-pagan movements like Wicca. Wicca is really a nature religion that sees a relationship between green spirituality and sexuality. Witches historically had less interaction with devils than with herbs, which they used as potions for healing and fertility. Cernunnos proved to be an ideal model for modern wiccans because of his relationship to the forest and his evident sexual vitality in mythic traditions.

However, medieval Christians began to use the figure of Cernunnos to pictorially represent Satan because of his horns and serpent, representing the evil one who seduced Eve into eating the forbidden fruit. Because of witches’ association with nature, they were associated with the horned nature god who was transformed into Satan. This did not prove a good association for witches in Western Europe in the late Middle Ages and up through the 17th century.

Wiccans venerate both a goddess and a horned god. Often the horned god in Wicca lore had a rams head rather than Cernunnos’ human head with stag antlers. But as the horned god of the forest in Celtic mythology he was a suitable candidate for marrying the goddess to bring about the return of spring and to ensure the fertility of the land. Goddess cults in world religions are almost always associated with nature and sexuality. In the Wicca view the horned god dies during the Fall as the vegetation and land go dormant, and in the Spring he is resurrected to impregnate the fertile goddess of the land. Cernunnos, like the Green Man, has been associated with seasonal variations. But in Celtic mythology he does not appear to be a dying and rising god like Adonis and his relationship with the goddess is a relatively new concept.

A variant of Cernunnos in Berkshire, England was Herne the hunter. Herne was also antlered, the god of the hunt. His assistance was important since people depended on killing a stag, especially in the fall, so there would be meat for the coming winter. The legend of the human Herne is that he was a favorite hunter of King Richard II, which created jealousy among the king’s other hunters. One day they captured him and hung him in the forest. Since then, he haunts the Berkshire forests.

Cernunnos/Herne has been a god worshiped by wiccans, who were involved in fertility rites.

Sexuality of Trees

Plants reproduce just like animals do. Trees may be male or female.

The Green Man had his counterparts in wood sprites. The pre-Christian Celts believed that the divine pervaded every aspect of life, and that spirits were everywhere. These spirits tied human beings to nature. Irish bards used erotic language to describe the landscape, identifying it with various parts of a woman’s body. Hills were compared with breasts and valleys with vulvas.

Woodsprites may be male or female since trees may be make or female.

Wood sprites, along with water sprites, are often associated with faeries as miniature creatures. But faeries had magical powers. Wood sprites are the spirits of the forest and of the trees. Like the green men, they are often shown residing within trees or with tree-like features or with foliage wrapped around their bodies.

Tree Meditation

Trees are not only plants of enchantment, they are also good settings for meditation on the natural world. They have lessons to impart from their fretwork 0f branches and twigs, their columns of trunks and boughs, their leafy canopes that give cooling to the forest floor from the sun They withstand time and seasons, rain and draught, tornados and ice storms. In their branches are birds and small critters that share food and warn each other of danger. Rings mark the tree’s longevity. As you sit at its base you can also see the insects at work in the ground and in the plans and flowers that occupy the forest floor. You learn lessons of the ecosystem of the forest and of the life of the tree, how it preserves and protects, and is resilient to the changes in weather. What does it teach about the human relationship to Earth’s ecosystem and to the resilience of our life.

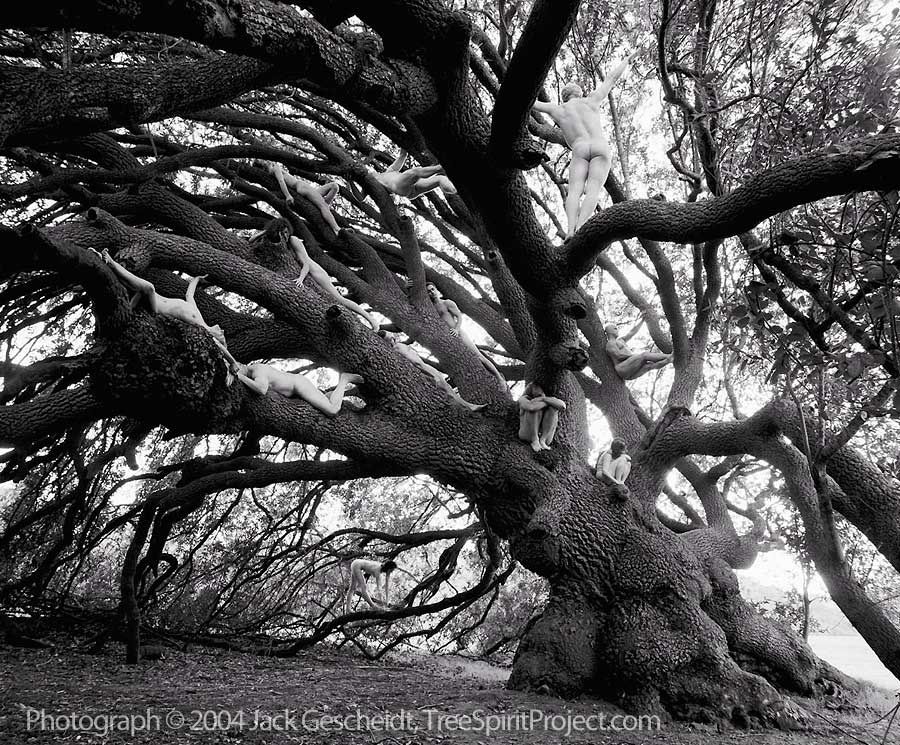

Protecting Trees

Trees require protection for Earth’s good and our own. An estimated 50-75 people took part in a staged protest on July 18, 2015 at a eucalyptus grove on the UC Berkeley campus, many of them stripping naked in doing so, to make clear their opposition to a proposed FEMA-funded tree-clearing program in the East Bay hills. Protecting trees and forests is an important activity of the Environmental Movement. Humans have a symbiotic relationship with trees. We breathe in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. Trees breathe in carbon dioxide and give off oxygen. Trees live in a symbiotic relationship with humans. We need to protect and manage our forests.

Our Green People

Finally, we should note the importance of “green” men and women in the modern world. Farmers who plant seed and nurture the growth of plants are our own vegetable people. Many farmers today are trying to grow crops organically without adding chemical pesticides and fertilizers that damage soils, water, air, and affect climate. Beyond this, however, there is a whole new field of research devoted agroecology: the science of managing farms as ecosystems. By working with nature rather than against it, farms using agroecological principles can avoid damaging ecological impacts without sacrificing productivity or profitability.

There are many ways in which we are becoming more environmentally aware. The ecosystem is an important thing to know since it is also our human environment. The Green Man and his friends can perhaps enchant us into relating to the natural world and taking care of it as good stewards. Perhaps we need green men on our church buildings. We need to pass on Earth and its ecosystem to the next generations. May the Green Man’s tribe increase!

Frank Senn