Question: In your book “Eucharistic Body” (Fortress Press, 2017), you argue against the practice of “radical hospitality,” in which Holy Communion is served to any who attend worship. Your argument is largely based on the need for “initiation.” What do you mean by “initiation” and why is it so important.

Answer: The question is about “initiation” as such—I assume both in general and Christian initiation in particular. So this answer will not be about the practice of radical hospitality at the Communion table. I answered that question in “Frank Answers About Radical Intimacy in Holy Communion.”

The whole point of any ritual process of initiation is to engage initiates with the beliefs, practices, and values of their community. All we have to do is ask how well we are transmitting to new generations the beliefs, traditions, and values of our society or of our religious community to determine whether more intentional initiation is needed.

Traditionally, the beliefs, practices, and values of a social group are passed on by the elders of that group. The tutelage of the elders is not so much “book learning” as telling orally the stories (myths) of the community. The initiands are the subjects of ritual acts usually performed on their bodies and they are engaged in activities that are important to the life of the community. Only then do new members of the community understand the deep spiritual traditions and the truth of the beliefs that lie behind what otherwise is just the cultural facade of these beliefs and traditions.

In the 1985 film The Emerald Forest, a captured white boy raised by an Amazon tribe is initiated into the tribe after an ordeal of lying on the jungle floor being attacked by ants. He has died to boyhood and is now a man through the tribal rites of initiation.

Modern American and European cultures have unfortunately lost much of the universal tradition of initiation. Initiation is experienced by many in college fraternities and sororities. The processes and experiences of initiation are present in these Greek house rituals, although the hazing has sometimes gotten out of hand because there are no real “elders” (persons of age and wisdom) present to apply brakes as needed. But done with good natured fun the “ordeals” can provide bonding within the group.

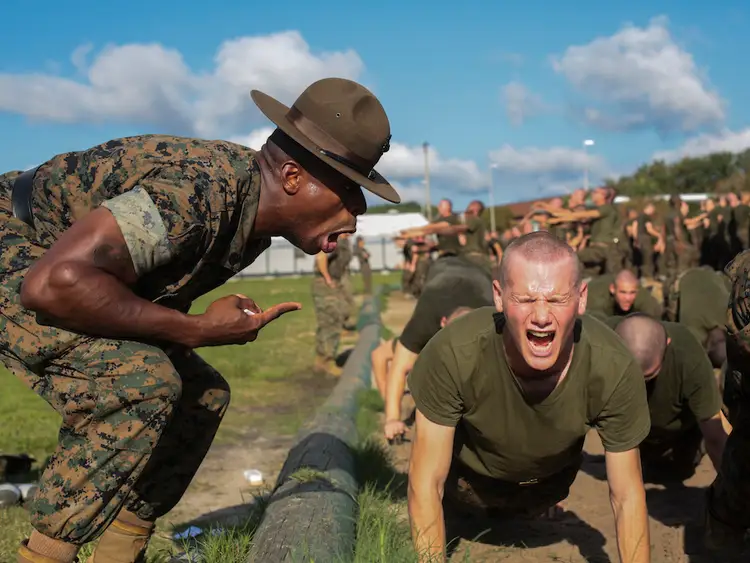

Adolescents are usually the subjects of rites of initiation. One adolescent ritual process in our society is learning how to drive. It is done in stages, with supervision at each stage, much like all ritual processes. True initiation involves an experience of powerlessness, the gradual bestowal of power as the initiate successfully passes each stage, and the wisdom that potentially comes with experiences of the use of power—whether that power is wielding weapons, applying knowledge, or receiving the keys to the family car. Without the experience of powerlessness, however, most individuals will misunderstand and probably abuse power. This is why the initiation experience of military boot camp is so important in forming soldiers.

Arnold Van Gennep, in The Rites of Passage (1908; English trans. University of Chicago Press, 1960), compared the process of initiation or life passages to taking a journey: leaving the place of origination/being separated from former roles or status; going on a journey/moving into a liminal or threshold space; arrival at one’s destination/being incorporated into the new community. Victor Turner, in The Ritual Process (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1969), focused on the liminal betwixt-and-between stage of transition because it is in unfamiliar territory that one has the possibility of an encounter with the sacred. Also, in the ordeals that a group of initiates undergo in the liminal situation a bond is formed among them that Turner calls communitas.

The group of initiates that goes through the ordeals together injects renewal into the whole social structure in which they are incorporated. This is best seen in educational processes such as enduring military boot camp and getting an academic degree. Those who go through such processes have the potential to renew society. This is precisely why a social group like the church needs to provide initiation. The rites of initiation are a constant source of renewal for the church as the Holy Spirit works faith in initiates through the sacraments of initiation. We need rites of initiation in both society and church.

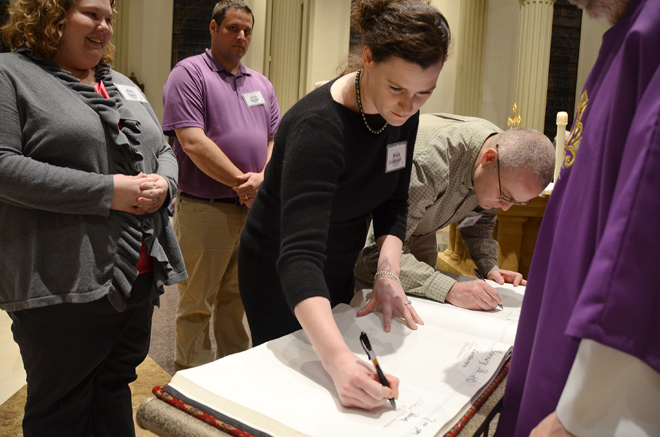

In the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA), those who desire baptism are enrolled as catechumens. They attend classes and are engaged in acts of ministry. At the beginning of Lent the catechumens who are ready to receive sacramental initiation are enrolled as elect, and their names are inscribed in the book of life. They will go through more intense preparation leading to Baptism, Confirmation, and First Communion at the Easter Vigil.

Franciscan Father Richard Rohr, in Adam’s Return: The Five Promises of Male Initiation (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 2004), discusses five learnings from the process of initiation: 1. Life is hard. 2. You are not that important. 3. Your life is not about you. 4. You are not in control. 5. You are going to die. He admits that these learnings seem negative and demanding to Western people. But they also represent what Christian discipleship is all about: 1. bearing the cross, 2. seeking first the kingdom of God, 3. serving God and the neighbor, 4. doing God’s will, 5. dying and rising in Christ. It is no wonder that Tertullian of Carthage said, “Christians are made, not born.” They are made in the crucible of the catechumenate.

Traditionally, the initiatory guides are elders. Christian catechumens are assigned mentors who will accompany them on their journey to and beyond Baptism. Unfortunately, in the West there are no longer communities with elders, only communities with the elderly. Elders are those who know how to pass on wisdom, model the identity of the community, and set the boundaries between the generations.

Initiation in traditional societies takes different forms for boys and girls. While both genders have to separate from their mothers, boys have the additional task of identifying with an entirely different gender. Boys not only have to become individuals apart from their mothers but masculine ones as well. Girls have to establish their difference from their mothers but not from their mother’s gender. In this one crucial sense, the developmental task for boys is more complicated for boys than it is for girls.

This is why rites of initiation for boys are more highly developed than for girls. One would think that fathers would help boys transition into male adulthood as mothers would help girls make the transition. But many boys have lacked fathers or father figures in their lives who can guide them into responsible male adulthood. Often their fathers also lacked initiation into responsible male adulthood. This often results in initiation by peers through street gangs and fraternities and often results in adolescent behavior that wreaks havoc on society, especially when young men act out their personal and social insecurities in acts of violence such as rape and shootings.

Both genders need initiation into adulthood. But boys need it more than girls says Dr. Michael Bader in Male Sexuality: Why Women Don’t Understand It — And Men Don’t Either (Bowman & Littlefield, 2008). His view is based on the supposition that the primary caregivers in our culture are usually women (mothers). The question is: how do children separate from women—mothers—and yet still maintain a loving relationship with them? How do boys become men, following adult masculine models, yet retain a love and respect for their mothers and for all other women in their lives? Basically, the question for male initiation is: how can masculinity be less toxic?

This becomes a real issue in male sexuality. We may have sex education in some of our schools, but no actual guidance in the experiences of sex. Boys either get their information from peers or pornography on the internet. Many boys are threatened by intimacy because expressions of tenderness seem so unmasculine and getting intimate with a girl makes them feel vulnerable. They are concerned about whether they will “perform” well enough. They can’t measure up to the dudes they watch on internet porn. (Who can? It’s unreal play acting!) Reliance on porn may even be a cause of erectile dysfunction in teen boys and young men. They may plunge into sex after drinking alcohol but then discover that alcohol relaxes muscles and gives them erectile dysfunction.

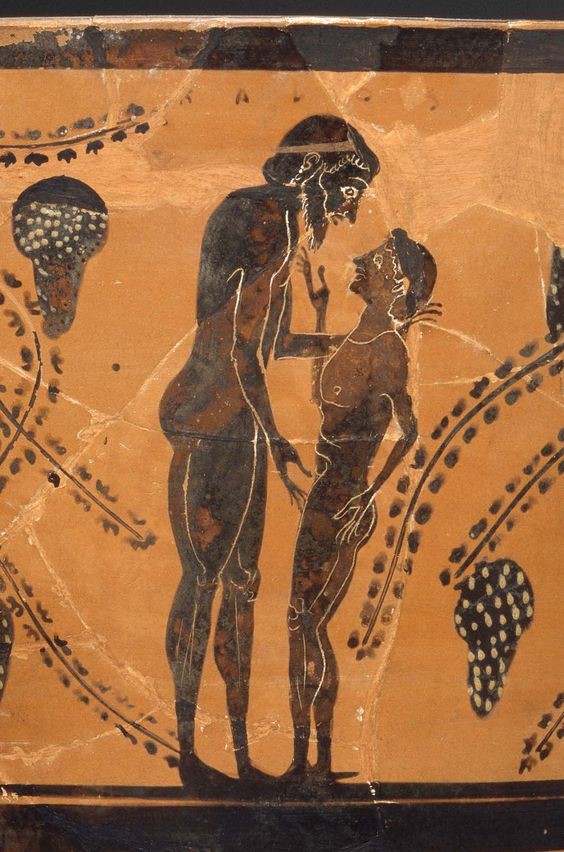

Many traditional societies had the elders or older men initiate the boys or younger men into sexual acts. Most well known is the practice of ancient Greece in which a boy had an adult mentor initiate his student into male sexuality. As the young men built up their sexual confidence and learned how to navigate socially they would make suitable husbands and fathers. In turn they they would take on a boy to mentor. (The Greek writers gave a lot of attention to man-boy relationships.)

This may have worked for the ancient Athenians but it’s obviously not a practice we would endorse in our society because of our aversion to pederasty. I’m not recommending it because, apart from any moral considerations, we lack the social history and cultural context in which the practice flourished. Our homophobia also causes us to reject any expressions of intimacy between boys and men and even between men and men. But our attitudes leave us without any form of initiation of boys into sexual maturity.

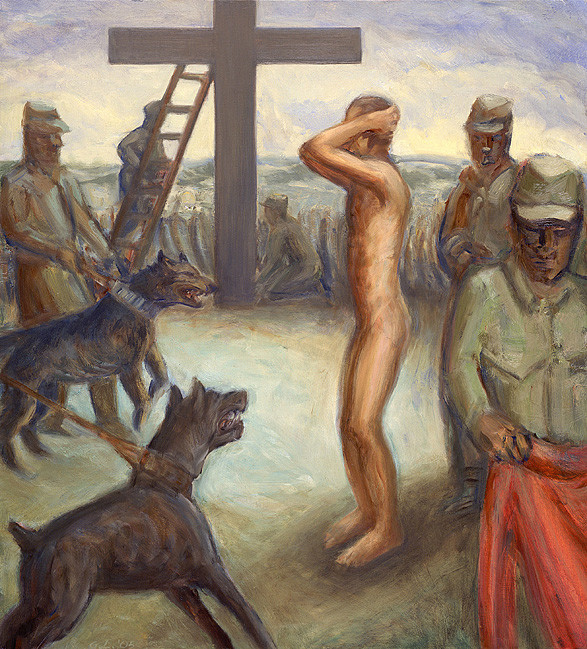

The church has not provided any resources that might address the needs of male initiation into social maturity. Symbols and images that might appeal to men are sometimes even suppressed in contemporary churches. Jungian analysts Robert Moore and Doug Gillette in King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of Mature Masculinity (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1990) proposes that men need images of the just ruler who embodies the right order of the universe, the heroic warrior who knows the fragility of life, the magician or wise guru who sees into the depths of human life, and the passionate lover who wants to be connected with other people to develop a mature masculine spirituality. Franciscan Father Richard Rohr, in Adam’s Return, suggests that Christian men need images of Christ as king/just ruler, as warrior/prophet, as guru/wise teacher, and as passionate lover of God and humanity. He writes: “Symbols for men have to be graphic, brutal, honest, hard, and almost archetypal or they will not break through the male wall of unconsciousness and denial.”

Some men have taken seriously the lack of adequate male initiation and try to provide rites of initiation for boys and men; for example, by giving them wilderness experiences with a high and strict set of expectations, including respect for others and for the earth. Most rites of initiation occur in natural settings, in wilderness areas, and usually entail nakedness. Thus initiates are placed in unaccustomed settings where their defenses are lowered and their vulnerability is exposed. They learn to depend on their guides, on one another, and on the creation itself.

The Headwaters Outdoor School at Mount Shasta, California provides wilderness rites of passage for boys. Most indigenous societies worldwide have various forms of initiation rites for both men and women. For women, these are usually fertility or puberty rites, as with the Navajo people—the Diné—whose Kinaalda ceremony ushers adolescent girls into womanhood. Young Native American males may be sent on vision quests. Surviving alone in the wilderness the initiate communes with nature and does not return to the village until he has faced death, drawn upon great inner and spiritual resources, and emerges knowing his calling. Jesus himself set an example for this by his own retreat of forty days of fasting and praying in the wilderness, replicating in himself Israel’s forty years of wandering in the wilderness and learning to depend on God’s grace alone.

Initiatory ordeals usually involve fasting and abstinence. The initiate learns to delay gratification in order to focus on higher pursuits. Being satiated with food and sex diminishes energy of body and mind needed for making judgments, engaging in combat, discerning choices in life, and ministering to others. Since the first century candidates for Baptism were required to fast. Fasting and practicing abstinence have been traditional requirements for receiving Holy Communion. The initiate learns to depend on the Spirit for guidance in surging forward or holding back.

The initiate often receives a new name as a result of his ordeals. But the initiates are not just named; historically, many initiates were marked on their body too, like Jacob being wounded in his hip by the angel who wrestled with him and gave him the new name of Israel (Genesis 32:26); or Saul of Tarsus was who was toppled from his horse and blinded on the road to Damascus and given his new name Paul; or Francis of Assisi who bore the stigmata (wounds of Christ). Being wounded and surviving helps us understand the pattern of life-death-resurrection. Many people who have had cancer or heart surgery have the scars of the surgery on their bodies as a reminder of the profound experience they went through. Wounded people are no longer simply victims but empowered to become wise healers (See Henri Nouwen, The Wounded Healer). No wonder the risen Christ still bears the marks of his wounds after his resurrection and ascension. I believe that the prevalence of tattoos and body piercings is a secular substitution for what young men and women once sought by fasting, circumcision, scarification, shaving of heads, and knocking out of teeth. [See Mircea Eliade, Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth , translated by Willard R. Trask (New York: Harper and Row, 1958).]

Traditional societies have highly developed rites of initiation. These adolescent Massai boys are preparing for their initiation as adult members of their tribe. They will go through the ordeals of initiation in which they transition from child to adult members of their tribe. As a result of initiation they will then take their place as warriors guarding the tribe. The old traditions are maintained over against the modern secular society that engulfs tribal life.

In the same way, the community of Christ must have rites of initiation that mark a transition from the old way of life to the new life in Christ. Christian initiation comes to focus in baptism. In the ancient church baptism was preceded by a catechumenate of some duration and intensity. Baptism was administered on naked candidates whose bodies were completely anointed with oil and immersed in the font. This immersion was followed by further anointing (seal of the Spirit) and the laying on of hands (by the bishop in the Western Church), the greeting of peace (for the first time) as a gesture of welcome into the eucharistic assembly, and first communion. Holy Communion is the goal of the ritual process of Christian initiation. It is full inclusion in the life of the church. Could one receive the body and blood of Christ into one’s own body and sense a connection with the whole body of Christ in heaven and on earth without having first gone through the entire process of Christian initiation?

This baptism is being performed at the Easter Vigil. By the fourth century the church had almost universally settled on Easter as the premier time of the church year to celebrate public baptism. Being immersed in the water and coming up from it signifies being joined to the death and resurrection of Christ. Pentecost became the second day for public baptism in the Western Church, since baptism is rebirth by water and the Holy Spirit (John 3:5). Those who were immersed in Christ’s death and resurrection and received his Spirit share in the meal that celebrates his death and resurrection and discern in faith Christ’s presence in the bread and wine according to his Word.

When the rite of confirmation was separated from baptism for reasons too complicated to discuss here, Pentecost became a preferred time to celebrate this rite of strengthening the gift of the Holy Spirit given in Holy Baptism. The laying on of hands is not just a bestowal of the Holy Spirit but a tactile gesture of being connected with the life and mission of the church. This is a reason why in the Western Church bishops as the chief pastors retained the prerogative of presiding at confirmations.

In Christian initiation one is “marked with the cross of Christ forever.” This is usually done with oil on the forehead. But Coptic and Ethiopian Christians historically had a cross tattoo marked on their body. Many young men have cross tattoos today. One would hope that these cross tattoos, and other religious emblems, carry religious significance for those who embody them.

The problem we face is that as we try to renew Christian initiation with the Rites of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) with its institution of the catechumenate, and use this as a model to which child initiation needs to be adapted (rather than the other way around), we live in a society in which initiation (especially of youth) is catch-as-catch-can. There is little frame of reference for the rigors or the necessity of initiation. Initiation is not just about ordeals (taking boys on a raft trip down the Colorado or serving a stint in the military or passing an examination); it is about becoming aware of mystery and attuned to wisdom. It is about perceiving a different way of doing the world as we make our way through life in this world to the life of the world to come.

In Christian initiation one’s values have been upended by the values of the kingdom of God. We know from the experience of initiation that we must make this pilgrimage into the Kingdom in the company of others and not just as individuals and that the Eucharist is food for the journey—for this journey into the Kingdom, and for none other.

Pastor Frank Senn