Question: If Jesus was stripped for crucifixion, and his clothes were divided and taken by the soldiers, and his body was wrapped in linens after his death for a quick burial, and the linens were left in the tomb when he rose from the dead, where did he get clothes to wear when he greeted Mary Magdalene and the apostles?

Good question. Of course, the truthful answer is that we don’t know. The gospel texts don’t tell us. I could leave my answer at that. But pondering the question further is a good exercise in biblical interpretation and an exploration of Christian artistic imagination.

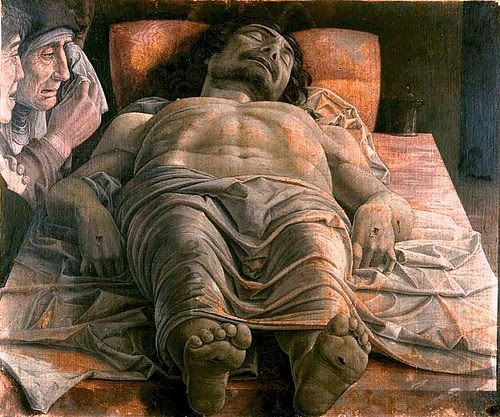

The Gospel of John says explicitly that Simon Peter “saw the linen wrappings lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself” (20:6-7) when he went into the tomb to look around. So Jesus wasn’t wrapped in burial linens when he emerged from the tomb. We’re even assuming that Jesus was wearing something when he greeted people after his resurrection because, well, we can’t imagine him greeting people while naked, and because that’s the way the artists have portrayed him. However, he’s usually portrayed as wrapped in a toga-like garment after his resurrection rather than in the tunic and mantel we know he wore during his earthly ministry.

Let’s deal with several issues separately: first, Jesus’ nakedness in the resurrection; second, how he would have gotten something to wear; and third, what Jesus’ Easter (that is, post-resurrection) clothes might have been. Finally, we will consider the implication of Jesus’ Easter clothes for us.

First, did Jesus come forth from the tomb wearing anything? It is unlikely that he had a suit of clothes in the tomb because his tunic and mantel had been taken by the Roman soldiers in the execution squad. In the typical burial custom his body would have been laid naked on a slab and wrapped in a linen cloth.

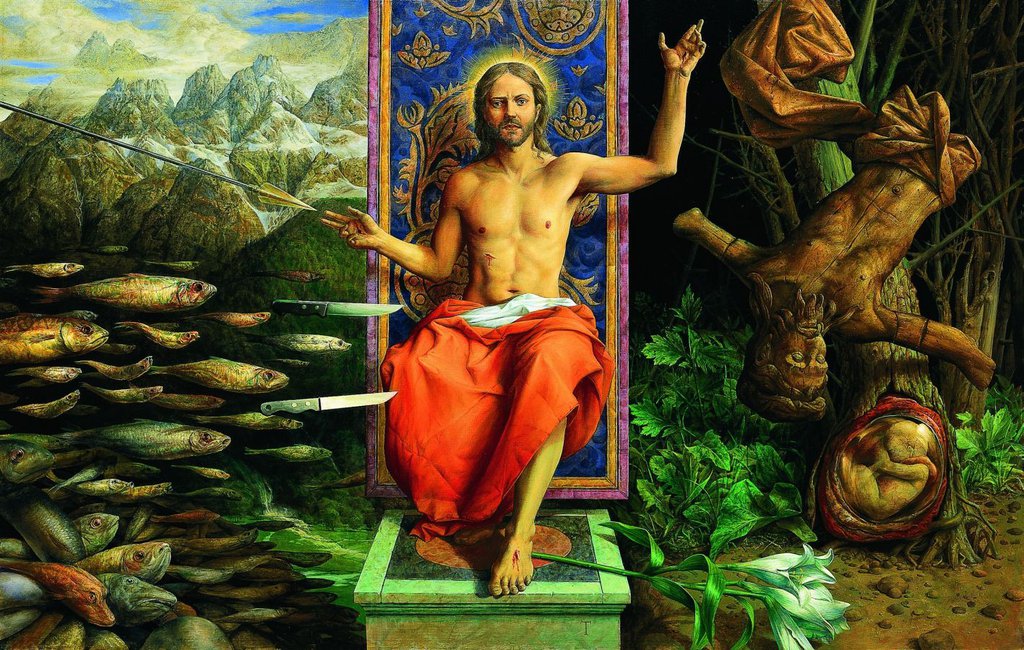

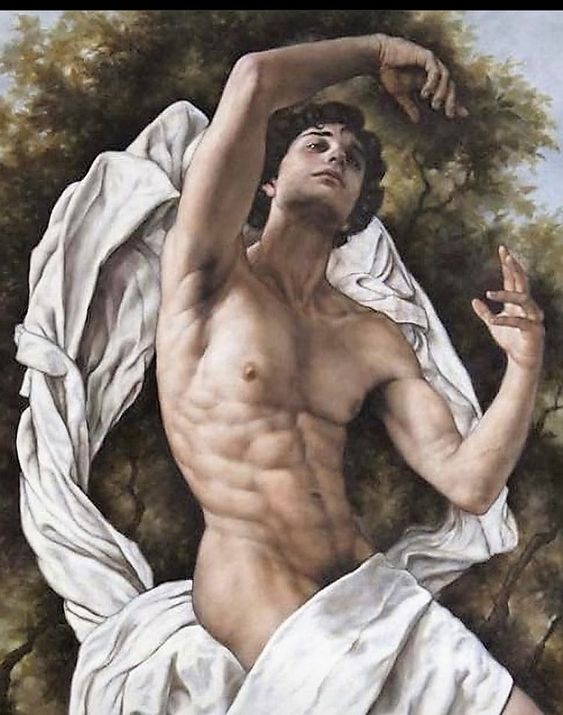

Jesus’ grave cloths (wrappings) were thrown aside as he rose from the dead. This painting of “The Dance of Eros” by Giorgio Dante is a good illustration. Eros is a good concept for the resurrection. The passionate love of God embraces the Son of the Father with new life and vitality.

So Michelangelo was surely correct to imagine in his statue of The Risen Christ (1521) that was placed in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva that Jesus emerged from the tomb naked. However, a century later a puritan pope had the genitals covered with a bronze drape that hangs improbably on the figure’s body, undoubtedly representing the linen cloths falling off his body.

However, there is an older version of The Risen Christ which Michelangelo began in 1514. As he was finishing it he found an imperfection in the top of the marble block and put it aside, leaving it for a student to apply the finishing touches. This sculpture of Christ rising from the tomb was completely nude, like the later one that Michelangelo did finish; but it was not set up in a church and Christ’s genitals were never covered.

This early version of The Risen Christ shows a muscular, confident Jesus holding the burial linens in his left hand so as to make the point that he had no need of a covering. Indeed, St. Paul would say that Christ was clothed with a “spiritual body” (1 Corinthians 15:44), which does not mean his body was lacking corporeal reality (he was able to eat with his apostles). As late as 1533 Michelangelo drew a sketch of Christ rising from the tomb in all his corporeal vitality with the linen burial wrapping falling off.

There’s no doubt that Michelangelo drew upon statues of Greek gods to portray the risen Christ. The ancient Greek gods were usually portrayed nude, such as this 1st or 2nd c. AD Roman marble statue of Hermes, copied from a Greek statue of the 5th-4th c. BC.

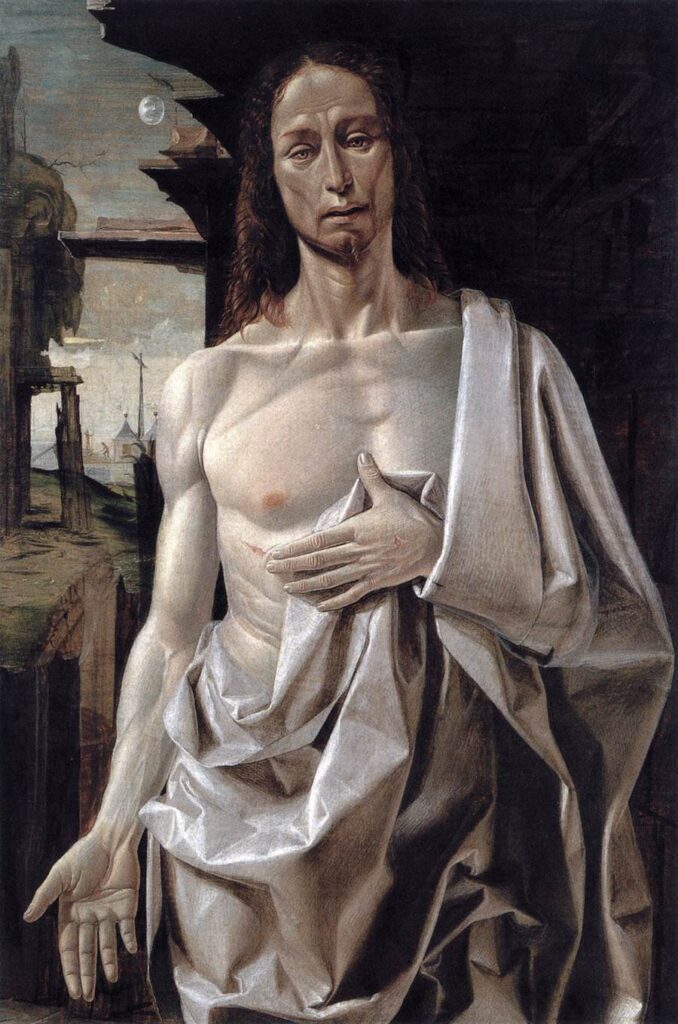

Michael Triegel is a prominent contemporary German artist who is attracted to religious and church art. His style reflects the old Renaissance masters. He painted a naked Christ rising from the tomb and leaving his grave clothes behind, as the Gospels record. This panting was displayed in the Museum of the Wurzburg Cathedral. But it was ordered to be removed by the cathedral authorities.

But the question remains: did Jesus have something to put on when he greeted people? We assume he did only because we can’t imagine Christ being naked, even with a “spiritual body.”

In the 20th chapter of St. John’s Gospel Mary Magdalene encounters the risen Jesus in the garden but doesn’t recognize him at first and thought he was the gardener. The failure of the disciples to recognize the risen Christ at first is consistent in the post-resurrection stories in the gospels. In her grief Mary Magdalene might not have noticed if Jesus was naked; a gardener might have been stripped to a loin cloth for digging or hoeing. In any event, Jesus told Mary Magdalene not to hold on to him because he had not yet ascended to the Father. His commission to her was to tell the disciples that he was ascending to his Father and their Father.

In decorating the cells of the Dominican monastery of San Marco in Florence, Fra Angelico and his assistants chose Mary Magdalene’s encounter with the risen Christ as the subject for cell number one. In this depiction (designed by Fra Angelico but probably painted by his assistant Benozzo Gozzoli in 1440), Jesus carries a gardener’s hoe, suggesting that he has work to do. He is wearing a toga that has been tucked in at the waist but no tunic or undergarments.

In the Gospel of John Jesus’ resurrection and ascension occurred on the same day. This would suggest that all of Jesus’ appearances after his encounter with Mary Magdalene was not only after his resurrection but also after his ascension. So he wasn’t wandering around on earth but was appearing from heaven whenever he greeted the apostles and others. He could have emerged from the tomb naked but was suitably clothed with heavenly attire when he met with his apostles and disciples. Some paintings of the Ascension of Jesus portray Jesus loosing his wrap (toga?) as he disappeared into the cloud.

But, second, if Jesus did have something to wear on the day of his resurrection when he greeted Mary Magdalene and the apostles, could someone have brought him a suitable garment? Throughout the passion stories people other than the chosen twelve disciples are taking care of his needs. Someone behind the scenes arranged for Jesus to procure a colt or donkey on which to ride into Jerusalem. Someone behind the scenes arranged for the upper room in which Jesus observed the Passover Seder with the twelve. We know the names of some of Jesus’s friends, admirers, and secret disciples from the four gospel narratives. There’s Mary and Martha and Lazarus of Bethany. There’s Joseph of Arimathea, who requested permission from Pontius Pilate to take down Jesus’s body from the cross and not have it left on the cross (as was Roman custom). He also provided the tomb. There’s Nicodemus, who had come to Jesus by night to discuss spiritual matters, and who provided the burial supplies. Did any of these people believe that Jesus would rise from the dead on the third day, as he had prophesied, and leave some garments in the tomb at the time of Jesus’ burial? Did an angel bring something for Jesus to wear when the stone was rolled away? What about the young man in Mark’s Gospel who was sitting on the burial slab when the three women arrived early in the morning on the third day? Did he expect Jesus’s resurrection and bring some attire for him to wear?

In all four gospels someone is at the tomb to announce to the women who came early in the morning on the first day of the week to prepare the body for a proper burial, that Jesus had risen and gone ahead of them back to Galilee. In Matthew, there was a fearsome angel. In Mark, it was a young man in a white robe. Presumably this is the same young man who came out from the baths the night of Jesus’ arrest to see the commotion and lost his linen towel in the melee and ran off naked into the night. Commentators have assumed this is the evangelist. In Luke, there are two men in dazzling apparel. In John, Mary Magdalene, consumed by grief, goes alone to the tomb and sees two angels. Someone—man or angel—was present at the resurrection to announce it to those who came to the now empty tomb.

We find it difficult to imagine Jesus meeting up with his disciples after the resurrection with wearing some covering. In Luke’s Gospel Jesus walked with his two disciples to Emmaus where they stopped for supper. Surely he was dressed, although perhaps not in his usual attire since the disciples recognized him only in the breaking of bread. In John’s Gospel Jesus had to reconcile with his failed disciples and give them a commission to go as his apostles into all the world with his gospel. Surely, we think, he must have worn something when meeting with them on the seashore in Galilee (although, like Peter, the disciples may have been naked for work—fishing).

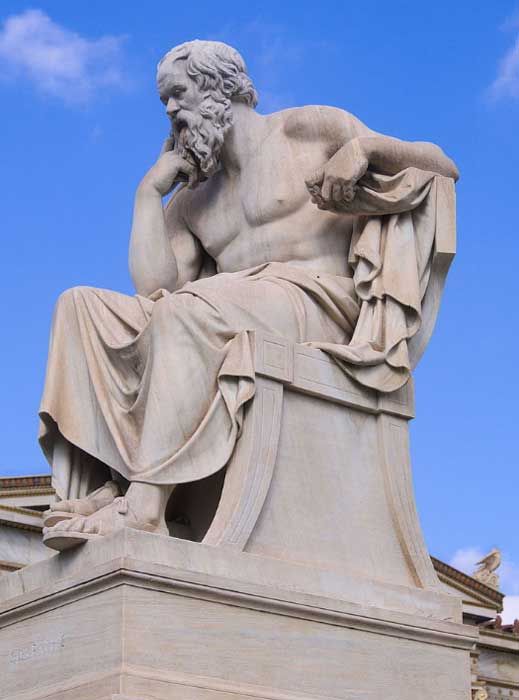

Since we are imagining that Jesus wore some covering after his resurrection, would he have continued to wear ordinary men’s garments or something fancier and more festive to celebrate the new reality that dawned in the empty tomb? We tend to wear fancier clothing for festive celebrations. So artists are not wrong to portray the risen Jesus wearing something grander then the ordinary clothing he wore during his earthly ministry. The Italian artists in particular chose a toga. This was a large semi-circular fabric that was usually draped over one shoulder and wrapped around the body. It was not a very practical garment and was usually worn only for ceremonial occasions. It might have been worn with a tunic, long or short. However, ancient paintings and sculptures of philosophers show the toga being worn without a tunic, the statue of Socrates below. So that is how the artists portrayed Jesus.

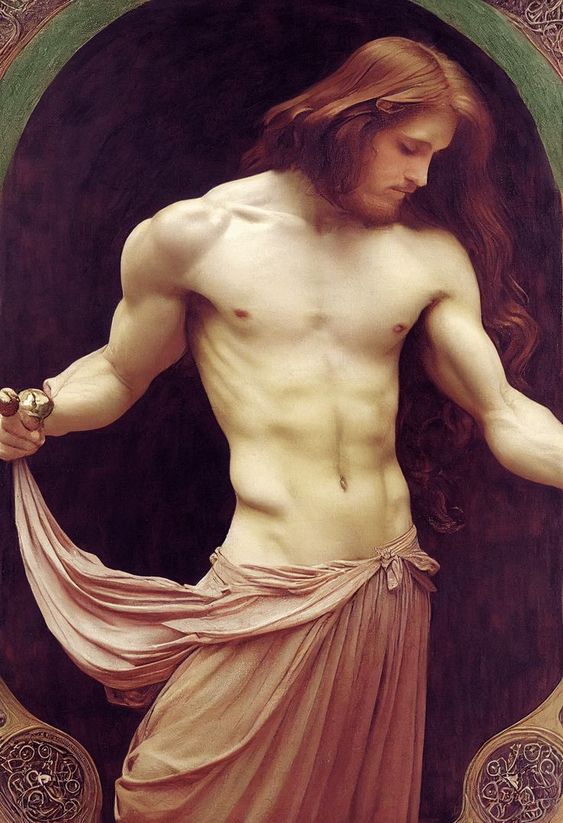

The following painting by Enrique Toribio, El Filosofo, depicts a naked Greek philosopher draped in a toga (minus the tattoos of the model). Actually, the Greeks favored a garment known as a himation, which was also put on by draping. One of the main differences between the himation and the toga was the bottom hem; the himation’s was straight, while the toga’s was curved. This was a convenient drape for philosophers who, like young men, spent a lot of time in the gymnasium where their prospective students were. Attendees at the gym were naked but put on a clean garment when they left at the end of the day, often to attend a dinner party. Could this have been a convenient wrap for the risen and ascended Christ who shared a meal with his disciples when he appeared to them?

In 2013 a painting of the risen Christ standing on the sealed tomb was identified as the work of the leading Venetian Renaissance artist Tiziano Vecelli, better known as Titian (c. 1488-1576), dated to about 1511. The large toga has been tucked in at the waist and could also be rolled up to expose the legs.

This renaissance painting of a young man putting on a toga that was fastened at the waist could have been a representation of the god Apollo. The post-resurrection portrayals of Jesus always include the marks of his wounds, so this is not Jesus. Nevertheless, Jesus and Apollo have frequently been compared. Apollo, the sun god, was the god of light and expression (often portrayed holding a harp). Christ was the sun of righteousness and the Word made flesh.

The portrayals of the risen Christ by these Italian Renaissance artists were undoubtedly inspired by statues of the ancient Greek and Roman gods, who are similarly loosely-attired in a toga. The Greek gods were also portrayed with long curly hair, which some artists have given to Jesus. Joan Taylor argues that the historical Jesus’ hair was probably cut shorter in the fashion of the first century and also kept his beard trimmed in the interest of hygiene (controlling lice). But the long hair favored by Renaissance artists attest to the beauty of holiness.

What Jesus might wear in heaven is a different matter. Would Christ have needed covering in heaven? Michelangelo portrayed a naked Christ descending from heaven in the mural of “The Last Judgment” above the altar of the Sistine Chapel. (The figure was later draped with a linen cloth with a linen concealing Christ’s genitals by order of a pope.) There has been a tradition of dressing the heavenly Christ in priestly robes for the celebration of the heavenly liturgy.

Likewise, in the ancient church the newly baptized emerged naked from the baptismal font as from a bath, which was often described as a tomb in the preaching of the church fathers, and were clothed in white tunics (albs) to take their place for the first time at the Eucharistic feast. Christian initiation came to be celebrated preeminently at the Easter Vigil. It may be in deference to the newly baptized putting on their new garments that the custom arose of Christians wearing new clothes to church on Easter Day. Can we see in the wearing of new clothes on Easter a renewal of our own Baptism as we gather “at the Lamb’s high feast?”

Wearing new clothes on Easter even became the opportunity for a procession. The origin of the famous Easter parade down Fifth Avenue in New York City was the procession of the members of Holy Communion Episcopal Church on Broadway who, under the leadership of their rector William Augustus. Muhlenberg in the 1840s, brought Easter flowers to the indigent patients of St. Luke’s Infirmary, which the parish had founded. (Muhlenberg was one of the first to place flowers on the altar in American churches.) The congregation was sent from the Easter liturgy to serve the Lord and love their neighbors, bringing with them the joy and hope of the gospel of Christ as they paraded in their new Easter clothes (and bonnets!) with flowers and gifts to gladden the lives of the poor and the sick. The idea of an Easter parade caught on and unfortunately, like many things, lost its original religious purpose as it became a major social event in New York and other cities.

We don’t seem to have Easter parades of people strolling down the street in their new Easter clothes, but maybe it’s an idea waiting to be revived for its original intent. We might conclude that Jesus had something new to wear when he came forth from the tomb. If so, that’s not without significance for us. If the risen Jesus had new clothes to wear when he greeted people, we might also wear new clothes as we celebrate the new reality that dawned on the day of resurrection.

In any event, the issue is not frivolous. Clothing is more than utilitarian. What we wear communicates important symbolic messages, not only about the wearer (e.g., identity, status) but also the activity or event for which particular clothing is worn. Lack of clothing is also symbolically significant. We tend to think of nakedness as symbolizing shame. But Jesus, naked on the cross and in rising from the dead, shows shamelessness. Unlike the first Adam, he has no reason to hide from God because he is the sinless Son of God.

Pastor Frank Senn