Question: Would having Black church art in our churches put a dent in White supremacy in both White and Black Churches?

Answer: Juneteenth, observed on June 19, was the final emancipation of enslaved Americans in Texas in 1865. This article encourages the emancipation of Black church art for display in all churches. the announcement of the emancipation of the slaves Galveston, Texas on June 19, 2029 was overdue (President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863), so is having a Black Christ in Black churches overdue. I’m sure including Black church art in all churches would put a dent in the ideology of white supremacy as far as Christianity is concerned. Jesus was not a white American. He wasn’t a European either.

The American philosopher John Dewey proposed in Art as Experience (1934) that art makes meaning by representing life as we experience it. The meaning we derive from art is related to our visceral or bodily experience of the world. So, it’s not surprising that even our religious art, while created as a response to scriptural stories and teachings, places our experience of the world into it. This goes deeper than simply dressing the biblical characters and scenes in clothing and landscapes familiar to us, as late medieval and Renaissance paintings did, or sculpturing the faces of our neighbors on the facades of cathedrals.

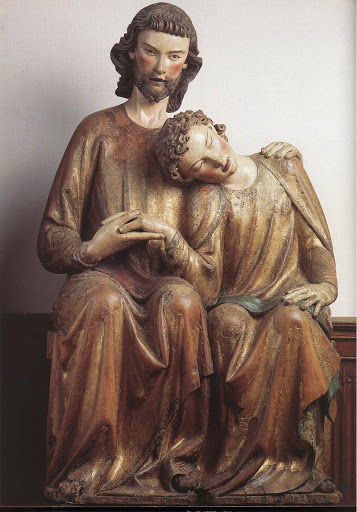

We can have art in the church because “the Word (Logos) was made flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace of truth” (John 1:14). We cannot have images of the invisible God, but we can have images of Christ because “he is the image (ikon) of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15). In fact, the Second Council of Nicaea (Seventh Ecumenical Council, 787) decreed that there should be an image of Christ in every church as an affirmation of the incarnation.

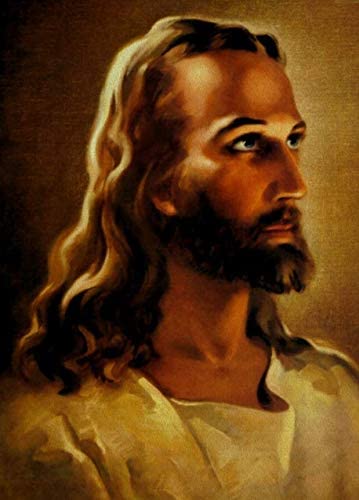

The representations of Jesus we are most familiar with are of a White Jesus. In fact, the most ubiquitous artistic portrayal of Jesus the Christ in American churches, Black as well as White, is Warner Sallman’s blue-eyed, blond-haired “Head of Christ” from 1940. It was a Christ who reflected white northern European Americans. In fact, Tallman’s original sketch appeared on the cover of the Covenant Companion magazine of the Swedish Covenant Church in 1928 and the finished painting was a gift to North Park University in Chicago. A Chicago-born former commercial artist who created art for advertising campaigns, Sallman successfully marketed this picture worldwide through two publishing companies, one Catholic, the other Protestant. It has been reproduced in art hung on walls in churches and homes and on billions of prayer cards. Tallman’s Head of Christ has become every American’s image of Christ, and it has hung in Black churches as well as White.

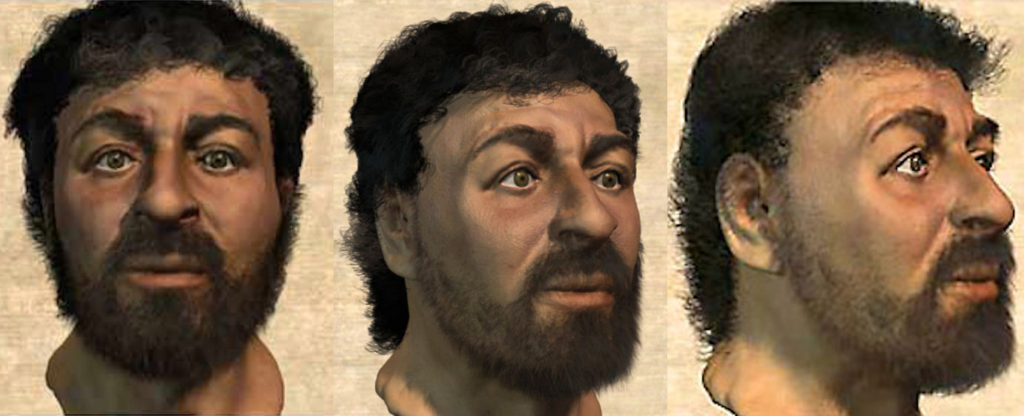

Of course, if we’re interested in an historically more accurate depiction of Jesus as a first century Palestinian Jew, in fact, as a Judean born in Bethlehem and claiming descent from King David, Tallman’s representation really misses the mark. Joan E. Taylor did a lot of historical research for her book, What Did Jesus Look Like? (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), and concludes that he probably looked like an average Judean since no distinguishing physical features are commented on in the gospels. If Jesus were perceived as especially handsome or ugly or tall or short, this might have been commented on by the evangelists since it would have made an impression on people. King David’s ruddy handsomeness, for example, was mentioned in the David stories. Taylor proposes therefore that Jesus was probably about 5’5″ in height, muscular from work as a carpenter but slim from walking everywhere during his life and ministry, with olive brown skin from genes and being outdoors in the sun a lot, brown eyes, black somewhat curly hair, and perhaps a short beard. Since long hair and beards could attract lice if you’re wandering around and sleeping on the ground a lot, Jesus’ hair and beard were probably kept short.

Several artists have tried sketching what an historically accurate head of Christ might have looked like. This is one sketch from three angles.

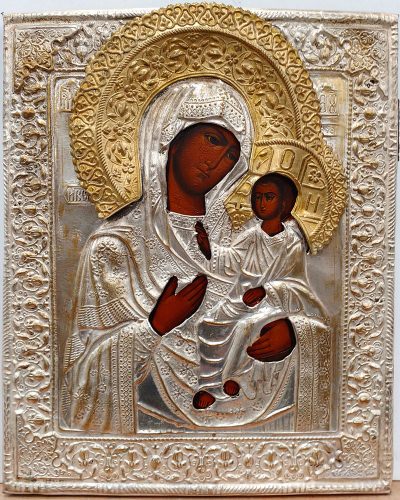

It is possible that traditional Greek Byzantine icons, for all their stylistic features, caught more of the Eastern Mediterranean Jesus with brown complexion than Italian and northern European Renaissance paintings of a pale faced Jesus. Notice that in this 13th century Byzantine icon the faces are more brown than white.

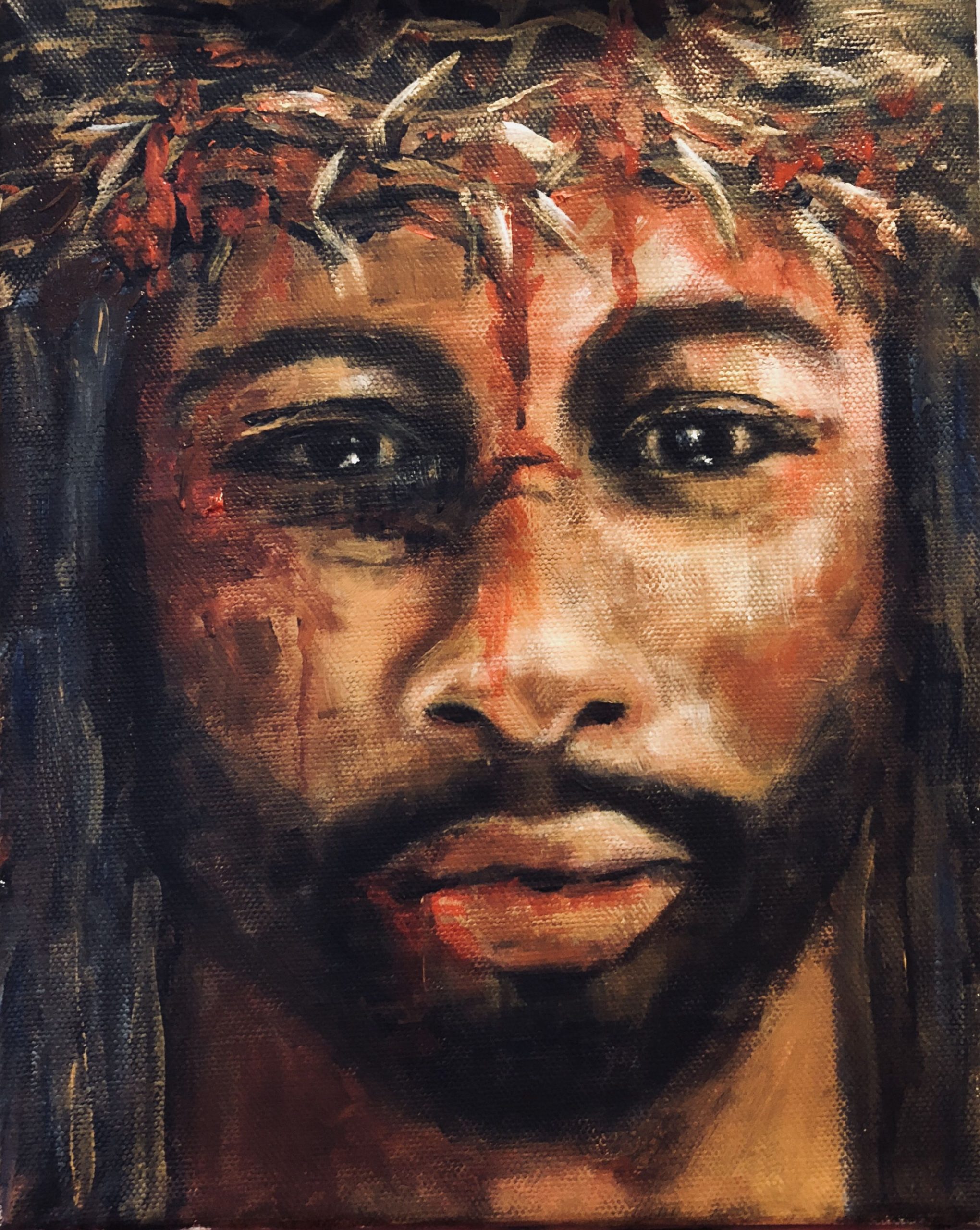

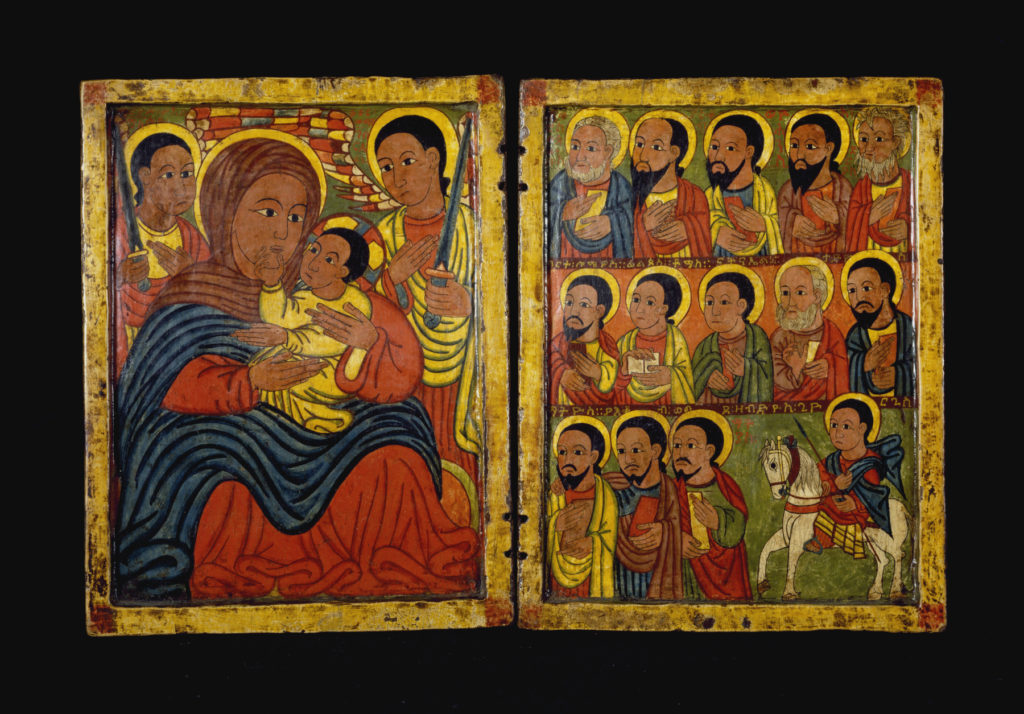

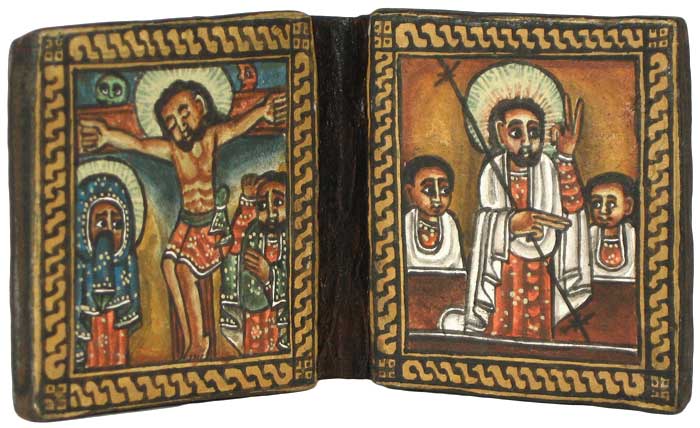

Of course, the Christ is universal only by being particular to all people. We can’t condemn the Europeans for painting the Christ in their image. Nor can we reject the inculturation of Christ in the artistic expressions of all races and peoples. In fact, Black images of Jesus go way back in African history since Christianity was established in Egypt and Ethiopia already in the first centuries A.D.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has also produced contemporary icons with the character of folk art.

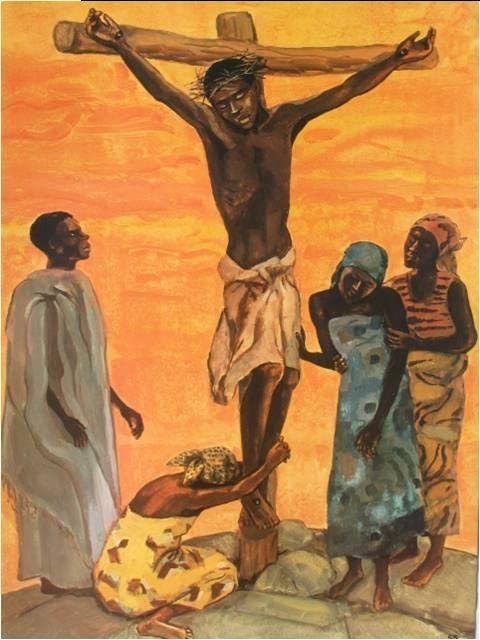

Not surprisingly, contemporary indigenous images of Christ abound in the African Churches today. The portrayal of a Black Jesus is no more off the mark than the blond Nordic Jesus presented in wall art and educational materials in white churches. The point of all artistic portrayals of Jesus is to show that he is one with us in human flesh and he is for us in his saving acts, as in this Mafa representation.

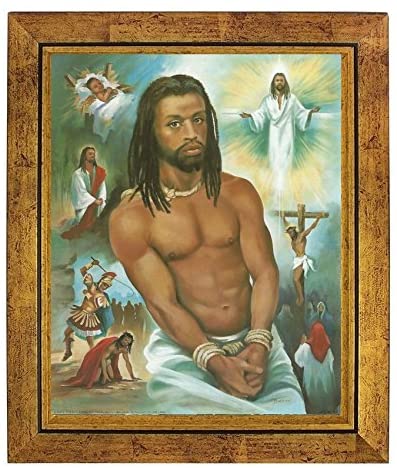

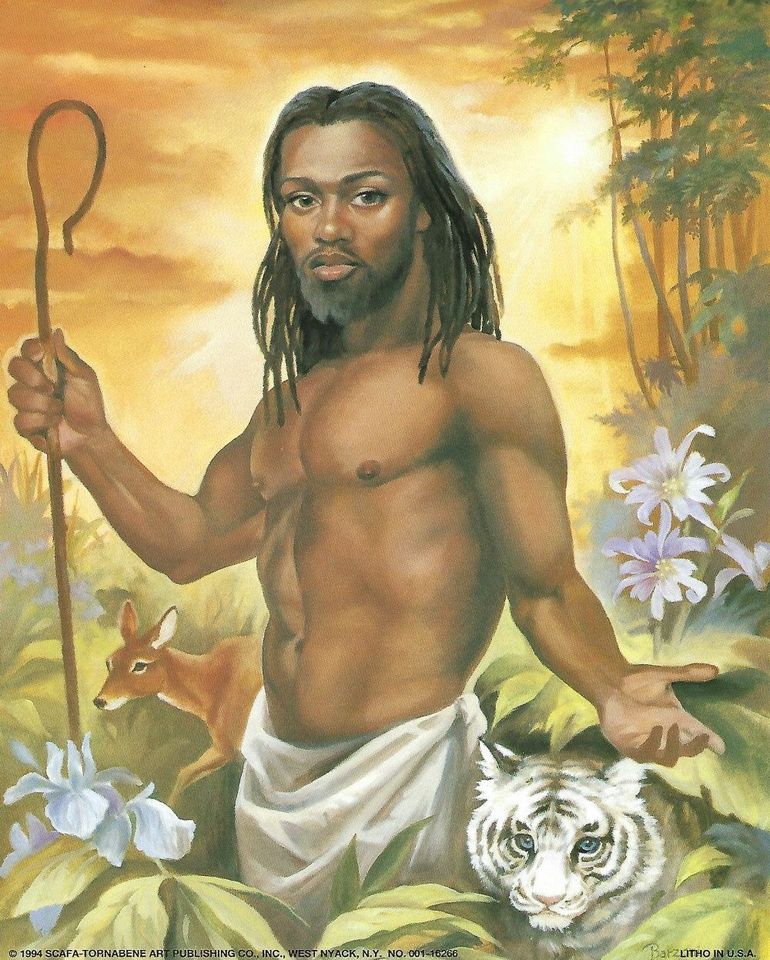

So why not an African American Christ? New York City born artist Vincent Barzoni, like Tallman, was employed as a commercial artist who won commissions from Abercrombie & Fitch, F.A.O. Schwartz, and the Audubon Society among others. Like Tallman, he also turned to religious subjects, including representations of Jesus that reflected the African American culture. This is Barzoni’s “His Voyage: Life of Jesus,” portraying Christ’s journey from his birth to his passion and resurrection. It’s interesting that the central figure of Jesus has bound hands as if in police custody.

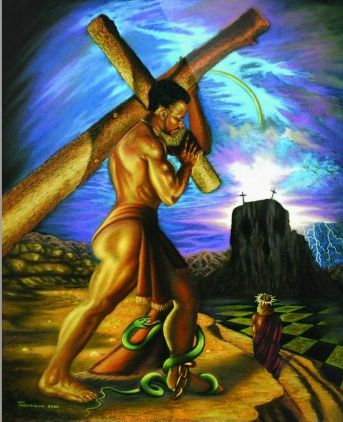

And why not African other figures in the Bible? Here is Alan Jones’ “Simeon of Cyrene” who was a visitor to Jerusalem pressed into service to carry Jesus’ cross when our Lord stumbled and fell.

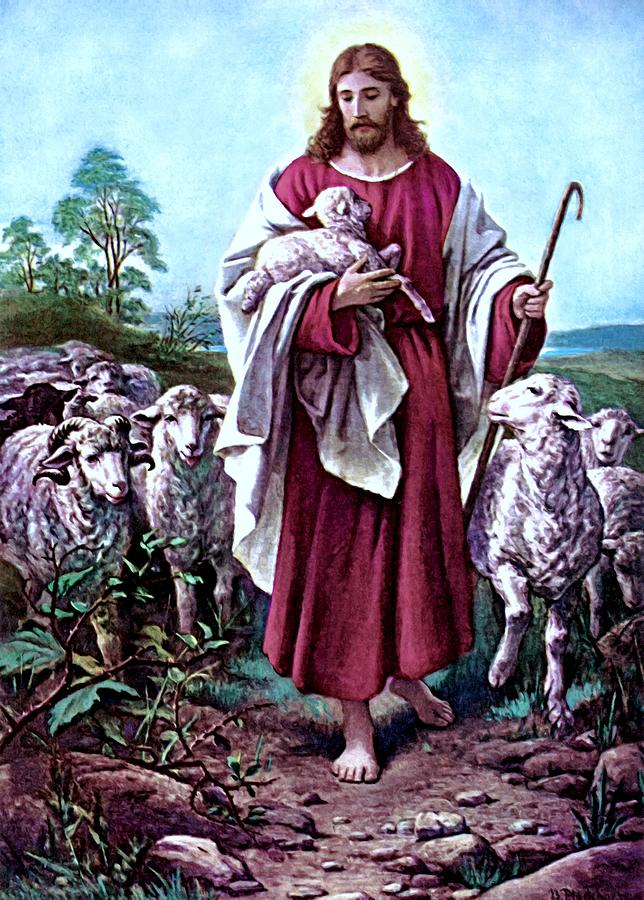

In the Lutheran church of my youth, a large painting representing Christ as the Good Shepherd was on the wall above the altar. My congregation was predominantly German American in its ethnic background and this portrayal was an expression of German romantic religious art by Bernhard Plockhorst (1878). It became almost as ubiquitous as Sallman’s Head of Christ and undoubtedly was featured also in some Black churches. Whether through Tallman’s Head or Plockhorst’s Shepherd, Black children would have grown up taking into their experience a blond hair, blue-eyed Jesus, thus reinforcing White supremacy. Subconsciously, both Blacks and Whites, exposed week after week to these representations of Jesus, would have had the notion of White supremacy reinforced, and it would have subconsciously contributed to a sense of White privilege. For Whites this would have meant that the Son of God is one of us.

But suppose the object of my devotion was this representation of Jesus the Good Shepherd by Vincent Barzoni?

African American features in this representation, in addition to the darker skin tone, include Jesus’ long hair braided into dredlocks. It’s interesting that there are no sheep in this painting. Other aspects of nature abound, including a white tiger, which is an endangered species. Barzoni’s representation of the Good Shepherd suggests God’s concern for the whole creation. If this representation was featured in my predominantly White church, I would at least have to consider that Jesus is God for all people. He is not exclusively “my Jesus” since he is portrayed other than like the White man I am. I will not presume to think about what impression this Good Shepherd would make on a Black Christian.

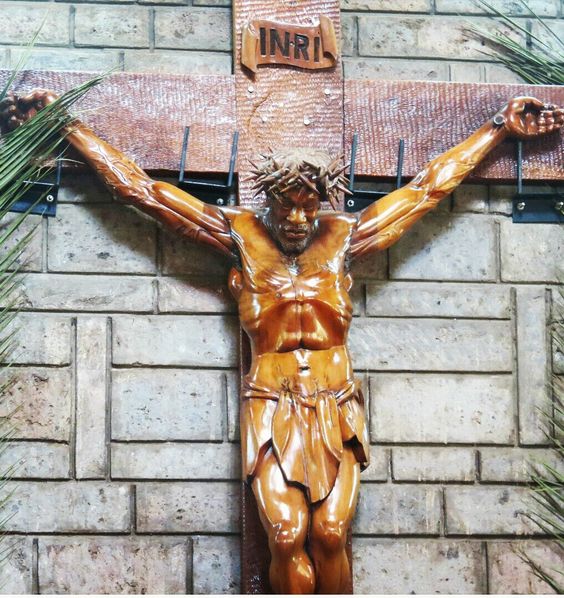

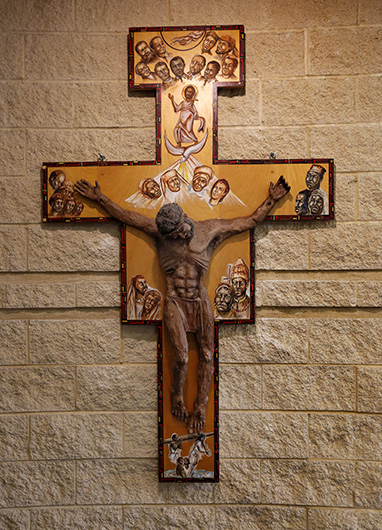

The way to alter embodied experience is to be confronted with new and different experiences. So, representing Jesus as African American would remove the idea of White Supremacy. The following crucifix and attending figures is on the wall of St. Benedict the African Catholic Church in Chicago. This is a predominantly Black parish. But White members of the parish and White visitors would encounter it. Would what brings comfort to Blacks present a challenge to Whites?

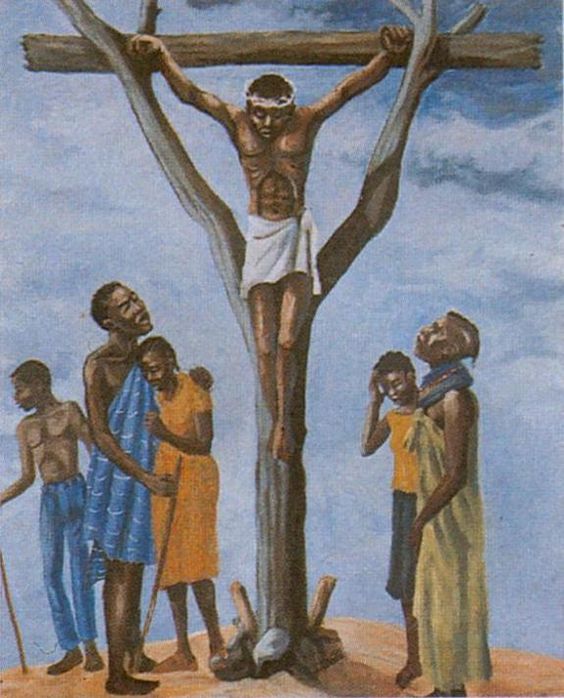

The African crucified Jesus among nomadic people (below) might also speak to African Americans because it has Jesus hanging literally on a tree. The African American Black theologian, James H. Cone, suggested that devotion to the crucified Christ is important to the spirituality of Black Christians because of their historical memory of the lynching tree in the early 20th century. Cone suggests that “Blacks told the story of Jesus’ Passion, as if they were at Golgotha suffering with him.” Whites too know the Spiritual, “Were you there when dey crucified my Lord? …when dey nailed him to de cross?…when dey pierced him in de side?…when de blood came twinklin’ down?” [James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (New York: Maryknoll Orbis Books, 2011), 73-74.] African Americans can feel the crucifixion of Christ so powerfully because his suffering is embodied, incarnated, in their own historical and physical experience.

If we experience the notion that Black lives matter through artistic representation, especially by encountering Jesus the Son of God as Black, the experience could cause us to reconsider our sense of White Supremacy. This would also help us to realize that the Jesus who relates even viscerally to all people founded a church that is “catholic” in the sense of embracing all people equally. There can be no special White privileges in the Church of Jesus Christ.

Pastor Frank Senn