The body has been an important field of study in just about every discipline. The old dichotomy between mind and body is no longer accepted. Neuroscience has increasingly demonstrated that the mind is part of the body, not a separate entity as Rene Descartes’ Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) implies. In their seminal work Mark Johnson and George Lakoff, Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought (New York: Basic Books, 1999), provide reasons from embodied mind theory for rejecting the Cartesian mind-body dualism in which the body is given lesser place to a disembodied mind and is often objectified along with the rest of material reality.

I have since discovered Mark Johnson’s later work, The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2007). In this book Mark Johnson goes beyond his pioneering work, begun in his earlier writings, to explore the deepest sources of human understanding, which lie in feelings, emotions, and bodily perception and motion. Philosophers have traditionally ignored these aspects of embodiment as source of meanings, focusing instead on more abstract conceptual structures. By pursuing such a focus modern philosophy has remained out of touch with new research in cognitive science, infant psychology, and the arts that show how images, emotions, and metaphors are rooted in our physical encounters with the world and yet provide the basis for all our human feats of abstract thought. The arts in particular are the culmination of human attempts to find meaning, and studying the aesthetic dimensions of our experience is crucial to unlocking the bodily sources of meaning. Making common cause with American pragmatist philosophy (e.g., John Dewey), Johnson explores the meaning(s) of the body from the perspectives of feeling, sciences of mind, and art and music, demonstrating by these examples that “meaning is more than words and deeper than concepts.”

Johnson’s work is important for liturgical studies, which has been my academic field. Attention to the meaning(s) of the body suggests that our apprehension of reality, including the realities of God and what the liturgical orders commemorate and celebrate, cannot be derived just from an analysis of literary texts. Liturgy is a sequence of ritual actions performed by and on the body.

Liturgy provides ways of acknowledging and expressing all five dimensions of the body’s meaning. I was pleased to see that I unknowingly followed Johnson’s schema of the body’s several meanings (pp. 274-78) in Embodied Liturgy: Lessons in Christian Ritual, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016).and in the order in which he lists them!

- The body as biological organism. The body must first be seen as a physical entity, a flesh-and-blood creature, living in the world. I actually began my first chapter with a review of the body’s physiological structure and biochemical composition and engaged the students in a meditative scan of their anatomical bodies. Throughout the book I kept returning to the body’s biological reality in its impact on rituals. Two big issues with impact on rituals are sex and death. Chapter 8, “Sexual Bodies, Dead Bodies,” deals with marriage and funeral liturgies.

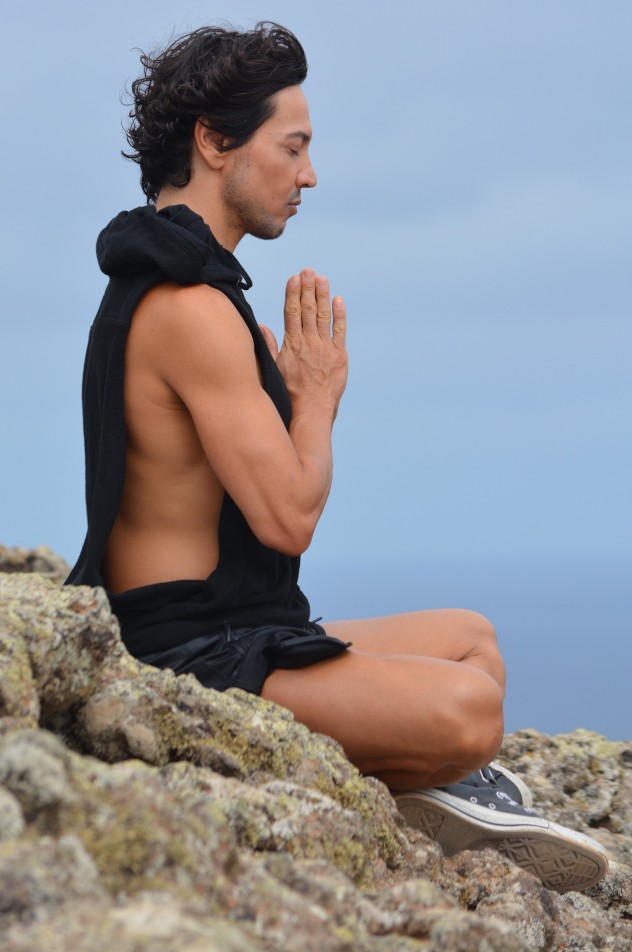

- The ecological body. The body is an organism within nature and functions in interaction with its natural environment. In chapter 2 I discuss the impact of natural rhythms on the circadian rhythms of the body (e.g. day and night, light and darkness). These rhythms form the basis of the daily prayer offices, especially morning and evening prayer. I led the students in a yoga sequence in which they enacted in their bodies the experience of following the course of a day from waking and being active to sleeping and resting and waking again.

- The phenomenological body. This is the body as we actually experience it. We experience it naked and enclothed. I dealt with this in Chapter 3, “Naked Bodies, Clothed Bodies”, which concerns rites of initiation and ministerial vestments. Chapter 6, Section B, “Penitential Bodies, Celebrating Bodies”, deals with the sensations of corporal penitence like flagellant processions and festivals that engage the lower body like carnival. We experience the body healthy and well. I included attention to rites of healing in Chapter 7 and gave attention to fitness and health in Chapter 12. I included a discussion in Chapter 3 of the yoga subtle body (the nadi and chakra system), with a related yoga practice, as a possible entrance into experiencing our psycho-physicality.

- The social body. Our body is both constrained and liberated by our social interactions. Society devised rules and regulations governing how the body is used in social settings. I dealt with this in Chapter 4, “Ritual and Play,” in terms of Mary Douglas’ schema of grid and group, and Johan Huizinga’s exploration of play. Chapter 5, “Sacrifices and Meals”, also deals with the social body since sharing the meat of the sacrifices and the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper are communal events.

- The cultural body. Our bodies are also constituted by cultural artifacts, institutions, and forms of expression. I deal with these cultural realities throughout much of the book, but especially the use of the body in cultural expressions in Chapter 9 (art and architecture), Chapter 10 (music), and Chapter 11 (dance and movement). Chapter 12 deals with liturgical performance and how the body is used in six different liturgical styles (Byzantine/Oriental, Catholic Traditional, Liturgical Renewal, Protestant Aesthetic, Protestant Revival/Seeker, and Pentecostal/Praise and Worship).

While I have highlighted the topics of certain chapters to emphasize particular aspects of the body’s meaning, Johnson insists that all five of these meanings of the body must be held together. The body is not just a biological machine and it is not just a cultural construct. It is all five of these meanings simultaneously. In this article I explore further this proposal of the multiple meanings of the body and expand on it.

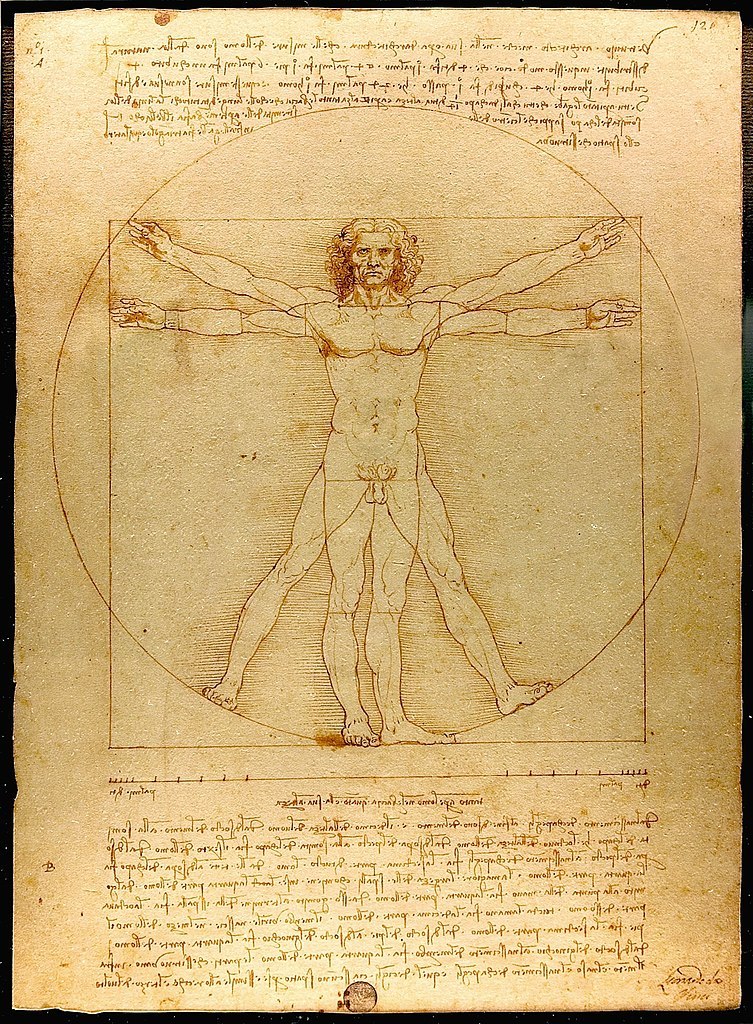

The Biological Body: Notes on The Vitruvian Man

The image above this article is Leonardo da Vinci’s famous “Vitruvian Man” from ca. 1487 that appeared in one of his notebooks. I chose it because it represents several meanings of the body. It brings together Leonardo’s interests as a scientist as well as an artist. The drawing includes notes from the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, who described the human body as the source of proportion in classical architecture. Da Vinci made notes on the anatomical proportions of the body, for example, noting that the span of both outstretched arms is equal to the body’s height. He also demonstrated the geometrical difficulty of placing a square in a circle. The center of the body in the circle is the navel; the center of the body in the square is the pelvis.

Apart from the geometric proportions of the body, in human embryology the growth of the body proceeds from the navel outward. Physiologically, the body’s structure is centered in the navel/pelvic region; muscles and ligaments flow to and from this area. If the mind is present throughout the body, the navel/pelvic area is a mind center as much as the brain. In decision-making we rely not only on the analytical “monkey mind” of the brain but also on “gut instincts”. The “Vitruvian Man” model places the navel/pelvic area at the human center.

Da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” has also been a constant inspiration to artists striving to express the beauty as well as the geometrical proportion of the human body. The following artistic rendering of the Vitruvian Man subtly demonstrates the square and the circle. This is a self-portrait by the Chilean artist Claudio Bravo painted in 1970. One of the signature features of Bravo’s paintings is the presence of packages and their wrappers. Perhaps it suggests removing the cultural wrappings to present the body as it naturally is.

The subtitle of Johnson’s The Meaning of the Body is “Aesthetics of Human Understanding.” He includes chapters on art and music. This is because art gives us a sense of the meaning of things that is not available in our everyday affairs. Although we sometimes enjoy the arts as forms of entertainment, visual and sonic arts also communicate meaning — including meanings about the body — without words. The meanings conveyed by art are non-conceptual and embodied. Claudio Bravo’s self-rendering as a Vitruvian Man is not a proposition that appeals to our thinking mind; it is an evocation summoning a visceral response.

The Ecological Body: Connections with Earth and Environment

The apprehension of sacramental reality requires a sense of connection with Earth and the nature we are a part of. We are created of the same material as Earth, which means we are created of the same material as our Sun. There is nothing in Earth that is not in our bodies. The classic four elements that ancient philosophy regarded as the composition of the cosmos — earth, water, air, and fire — are the composition of our bodies. We are created from the dust of the ground with all its chemicals, mixed with water (our bodies are about 65% H2O), enlivened by breath (oxygen), and given growth by the warmth of the sun. There is great value in reconnecting with Earth, body to body. The Earth is an electro-magnetic field that recharges our bodies through direct touch, at least by walking barefoot.

Our liturgical rites and sacramental ceremonies and symbols tap into these elements: wheat, grapes, and olives from the earth for bread, wine, and oil; water for the bath (baptism); the breath of the Spirit empowering words; the new fire of the Easter Vigil from which our candles are lighted; the candles themselves which are made of beeswax.

The Phenomenological Body: Experiences of Sexuality

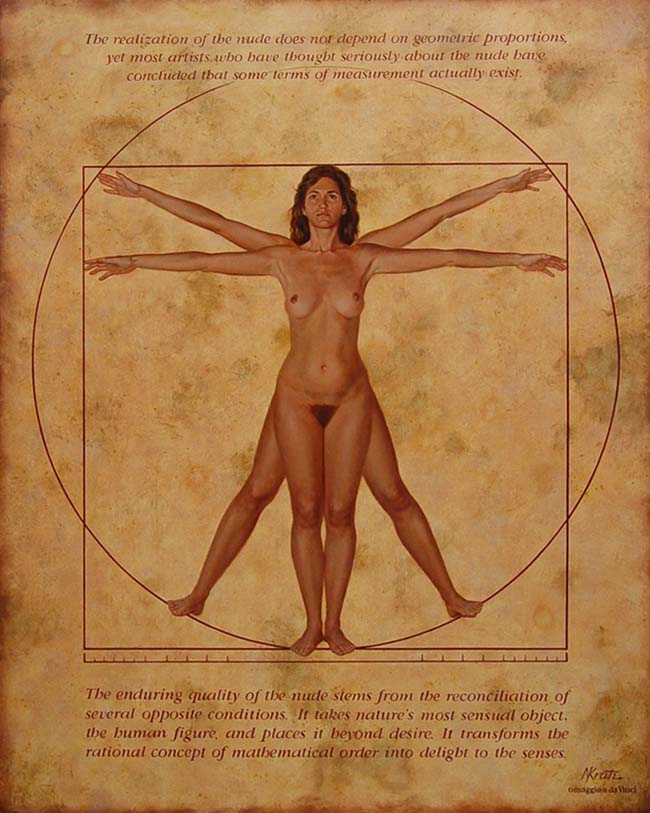

While I did not deal with gender issues in Embodied Liturgy, I did deal with the sexual differences of women’s bodies in relation to pregnancy. I referenced Theresa Berger’s experience of pregnancy in which she brought the waters of the womb and the waters of the font into intimate contact (pp. 188-89); also the need for post-natal care of women in relation to the old rite of the churching of women (pp. 207-12). Luce Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference, trans. Carolyn Burke and Gillian C. Gill (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993) pointed out the important biological as well as social and cultural differences between male and female bodies. Irigaray holds that no phenomenology of the body will be satisfactory that doesn’t recognize the fundamental biological differences and unique experiences women live in their bodies. American artist Nat Krate painted the Vitruvian Woman.

However, the sexuality of the body relates to all five meanings proposed by Johnson. Sex is biologically determined by chromosomes and genes and geared toward procreation. All Christians have emphasized the procreational function of sexuality. Sex is ecologically determined in terms of the availability of partners for coitus. Sex is phenomenologically experienced in terms of pain or pleasure. Sex is socially controlled in terms of what behavior is permitted or prohibited by law. Sex is culturally conditioned in terms of how sexual partners are expected to perform and what kind of sexual activities are acceptable. Marital sexual practices were tightly regulated through the confessional in medieval Catholicism. The Protestant reformers’ early discoveries of sexual and gender differences are noteworthy, but far different from contemporary experiences in which traditional gender roles and between men and women and restrictions on sexual practices have been all but obliterated. The woman in a dominant position would have “contrary to nature” among the ancient Greeks and Romans.

The Homosexual Exception

In recent years we have studied same-sex attraction and practices and discovered that it is found in animal species and in human societies throughout the world. Clinical sexology since the late 19th century has defined exclusively same-sex oriented males and females as heterosexual or homosexual. Scientists are still working on finding a biological basis for same-sex attraction. There’s no question that it is phenomenological in that persons respond to the feelings they have from sexual experiences. The ease of pursuing their desires is determined ecologically by the availability of suitable partners, socially by laws prohibiting or permitting same-sex relationships, and by cultural expressions of same-sex attractions in lifestyles which are now identified as “gay.” The revision of attitudes about homosexuality is slowly changing in churches as well as society. Some Protestant churches allow for the ordination of gay clergy and the blessing of same-sex marriages.

The Social Body: Honor/Shame Issues

The body has been the site of both honor and shame. In the Bible male and female were created in God’s image as the crown of creation. Adam and Eve became ashamed of their bodies—of themselves—as soon they transgressed the limits. Their shame went immediately to their genitals, where they most intimately express their relationship to each other, which they tried to cover with fig leaves. When our primal parents were expelled from paradise the Lord God, in an act of grace, fashioned garments from animal skins for Adam and Eve to provide both for their modesty and for warmth and comfort in the cold, hard world outside of the paradise garden. As a consequence nudity came to be associated with sin and shame in the Christian tradition. As we became an enclothed society with less and less instances of public nakedness in the modern West, nudity has become exclusively associated with sex. Sex itself has been viewed negatively except for the act of procreation. Our sexualized bodies are regarded as the source of evil and sin and must be hidden.

Some Renaissance artists, however, most famously Michelangelo, painted the primal couple leaving paradise still nude in his creation scenes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Perhaps as an artist who idealized the human body he believed that there is a residual honor to the body even after the fall. Also, a theological argument could be made that since an animal sacrifice would be needed to have skins with which to make garments for Adam and Eve, that had to be done outside of paradise.

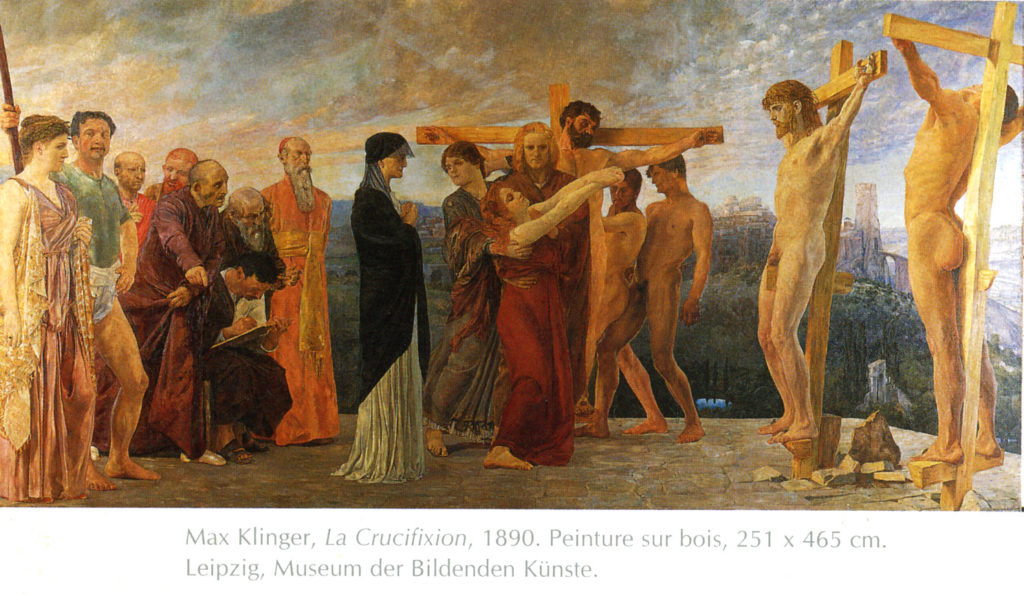

Christians believe that Christ, the new Adam, bore not just our sin but also our shame on the cross. In part this is because hanging naked in public is a form of punishment intended to bring shame to the victim. Roman floggings and crucifixions were done on naked bodies to inflict maximum humiliation. There is no doubt that Jesus was crucified totally naked, according to Roman custom; but as one who was innocent he had nothing to hide. Christ also brought honor to the human body by being God incarnated in a human body and rising bodily from the dead. (See “Frank Answers About the Body—God’s and Ours”)

Since writing Embodied Liturgy I have discovered the published doctoral dissertation of Vietnamese theologian Dan Le, The Naked Christ: An Atonement Model for a Body Obsessed Culture (Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2012). I wish I had known of it before I finished writing my book. He proposes the naked, suffering Christ on the cross as the answer to a body-obsessed culture — obsessed with commercial images of glamorous perfect bodies that most of us desire but cannot attain so that we are always disappointed with our bodies. He is also certain that Jesus’ genitals were not covered by a loin cloth on the cross. It is interesting that Professor Le and I have independently discovered the dialectic of nakedness/enclothed in the Bible, in theology, and in liturgy.

The Social Body and the Political Body

How we present our bodies in its social dimension is not just a social construct, it is also a political coercion. Michel Foucault holds that the body and its behavior are “constituted” by social norms and political coercive practices. In The History of Sexuality he shows ways in which society has acted to repress and control sexuality, often through its political structures. The Catholic Church exercised control of sex through its practices of penance (the confessional). Societies punished those who engaged in deviant sex like homosexuals or women (seldom men) who committed adultery. Over the last several centuries, science joined forces with social authorities to repress childhood masturbation, treat female “hysteria”, categorize various forms of deviant sexual behavior (fetishes) as “perverse” and design psychiatric treatments for them.

In considering the political body I should note that the amount of public nakedness and appropriate clothing have not only been a matter of social approval and cultural expression; these public presentations of the body have been enforced by law. It is usually illegal and subject to fines to expose one’s genitals (and sometimes nipples) in public. Since we in the West have lived in a clothed society, expressions of protest have involved public nakedness. One thinks of Francis of Assisi removing all his clothing and standing naked before the bishop of Gubbio, his father, and the merchant class to renounce wealth.

Scene of Francis of Assisi standing naked before the townspeople in the film Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972), directed by Franco Zeffirelli.

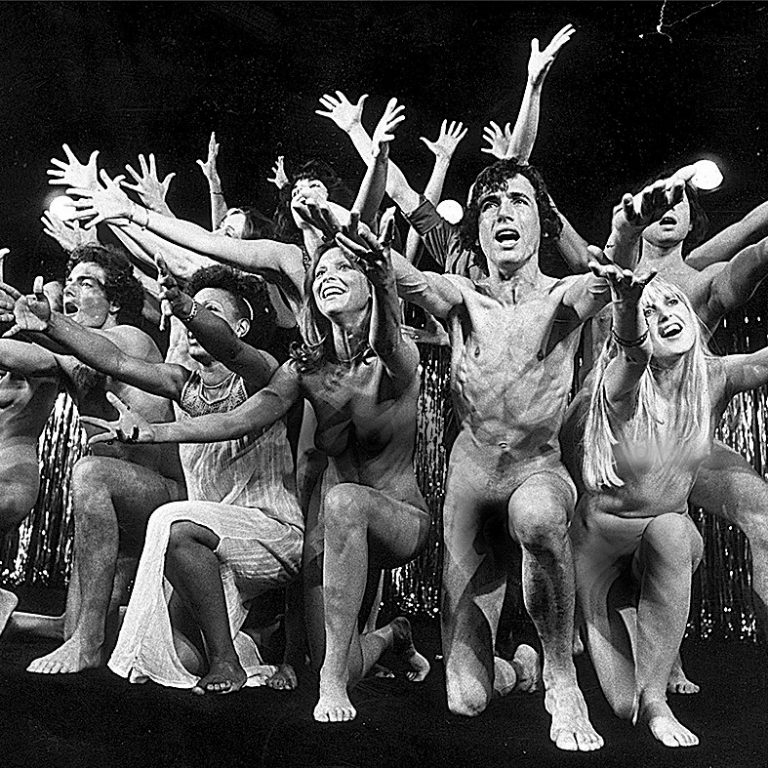

In the late 19060s Hair, the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical also caused a stir with its onstage nudity.

The Cultural Body: Gender Issues

Neither Johnson nor I dealt with gender issues. This is because gender was largely irrelevant to our projects. Gender does affect language and Johnson devoted a lot of attention to metaphor, especially with George Lakoff in Metaphors We Live By (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980). In their work Lakoff and Johnson demonstrate that metaphors are ways we structure our reasoning and our everyday language on the basis of our actual sensorimotor experiences. Those experiences of life in society and culture might make some metaphorical uses gender-specific. But that wasn’t the philosophic issue Lakoff and Johnson were pursuing.

My project was to explore the use of the body in liturgical and paraliturgical rites; I was not dealing with texts (the usual theater of liturgical gender wars) that accompany liturgical gestures, postures, and movement. Some rituals are gender-specific. But, for example, that boys might have a male equivalent of the Mexican Quinceanera, or that girls might participate in the Greek Orthodox diving for the cross, I will leave for those cultures to sort out. But these examples also indicate that gender is how the sexual body is presented affected by accepted and sometimes enforced social roles and cultural expressions.

Boys diving for the cross on Epiphany Day in Tarpon Springs, FL

However, I did introduce the yoga (Tantric) subtle body as a way of experiencing the body as something more than a biological machine. It allows us to sample the phenomenological body — the body as we experience it. The yoga subtle body invites us to consider the male-female duality/union that contributes to the gendering of the psychological body. The streams of energy called nadis (ida, pingala) that flow from each side of the brain (left/right) to the perineum along the central channel (sushumna) represent the lunar/solar, feminine/masculine energies of the human body. In most mythologies and archetypal psychology, the feminine aspect (lunar principle/left brain) is interested in intuition, harmony, connection, and relationships; the masculine aspect (solar principle/right brain) is interested in literalism and linearity. Not all women fully identify with the feminine principle, and not all men identify with the masculine principle. According to this yoga map of the body we all have elements of the feminine and masculine within us and undoubtedly lean toward one or the other in varying degrees.

The Cultural Body: Naked/Clothed Issues

Within my reflections on the body I have given attention to the naked body because that is how we feel our bodies most directly if we live in a clothed society. The dialectic of nakedness/enclothed provides another aspect of the body’s meaning, and it is a far more important meaning than we have generally considered.

On the one hand nakedness suggests innocence, truth (“baring all”), and vulnerability. On the other hand the naked body can be the subject of humiliation, shame, and punishment. Adam and Eve were attempting to hide their guilt from God when they grabbed some fig leaves in an attempt to cover their nakedness. They compounded their sin of eating the forbidden fruit by being ashamed of what God had created good. By covering their “private parts” they also demonstrated an alienation from God, from each other, and from the natural world.

Since “the fall” nakedness cannot stand alone; it needs to be considered in juxtaposition with clothing. Clothing provides both modesty and warmth, but dressing the body also provides a way of expressing festivity and personal identity. There is a new field of enclothed cognition that studies the impact of clothing on the wearer’s self-identity.

The dialectic nakedness/enclothed is a rich symbolism in many religions. Rites of initiation often include nakedness followed by being clothed in special garments. We have not given enough attention to the experience and meaning of either the naked body or the clothed body. In Chapter 3 in my book, Section A deals especially with circumcision and the ancient church’s practice of naked Baptism. The Section B deals with being vested in the white baptismal robe (alb) and in priestly vestments. We are properly naked before the Lord, and also dressed before the Lord in the vestments God provides.

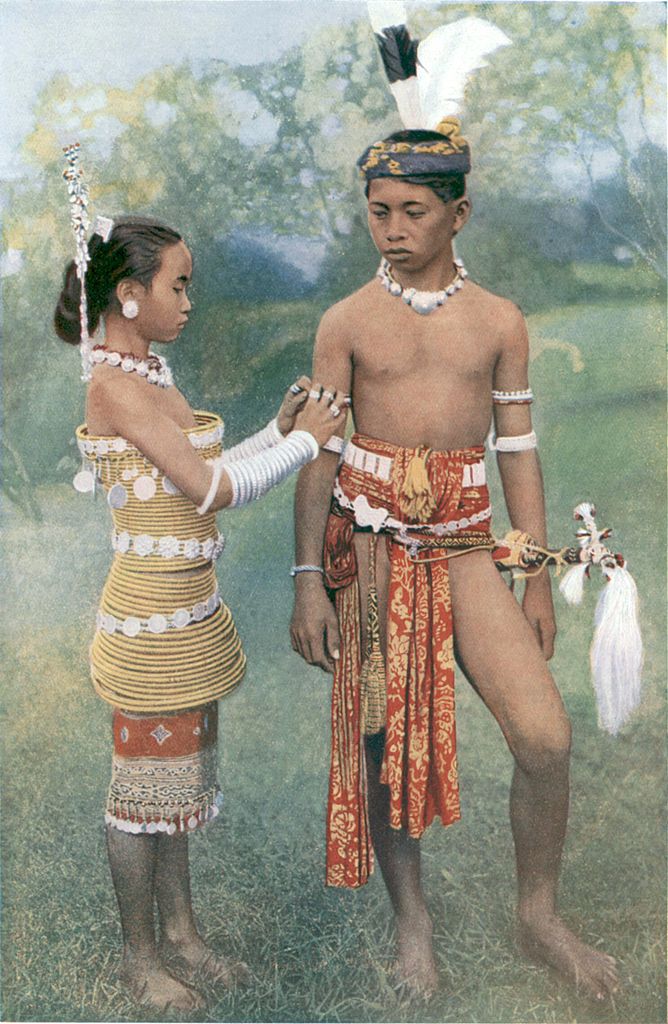

In terms of Mark Johnson’s schema, both nakedness and clothing are determined by biology, environment, phenomenology, society, and culture. We are, of course, born naked from the womb and are immediately wrapped in blankets. We are more or less naked or more or less clothed in daily life depending on the environmental conditions in which we live. Phenomenologically, we have stored in our bodies sensations of being both naked and clothed. We remember feeling the warmth of the sun and the cooling effects of a breeze on our skin on a hot summer day and also being bundled in warm outer clothing on a cold winter day. Socially, the degree of allowable public nudity and appropriate clothing are prescribed by the social context. Semi-nakedness is allowed on the beach but not in a restaurant off the boardwalk. Culture determines the style of clothing and body ornaments we wear. In my culture I wear pants and a shirt, and maybe a coat, but not a long robe. In some societies that wear less clothing festivities are celebrated by directly adorning the body, as in the example of young Ibans of the Sea Dayak people in Borneo (an image used in my book — here it is in color).

The Interpersonal Body

Liturgy is a corporate work. Our bodies relate to other bodies in the assembly and acquire a more than personal meaning. Merleau-Ponty spoke of the intersubjectivity of the body as it surges even from its emergence from the womb to connect subject-to-subject with other bodies and with the world into which one is born. Our intersubjective body connects with others through motoricity and sensation. We are attracted to others when we see what they are doing and we feel a connection with what others are doing and with them. This is how community happens and forms.

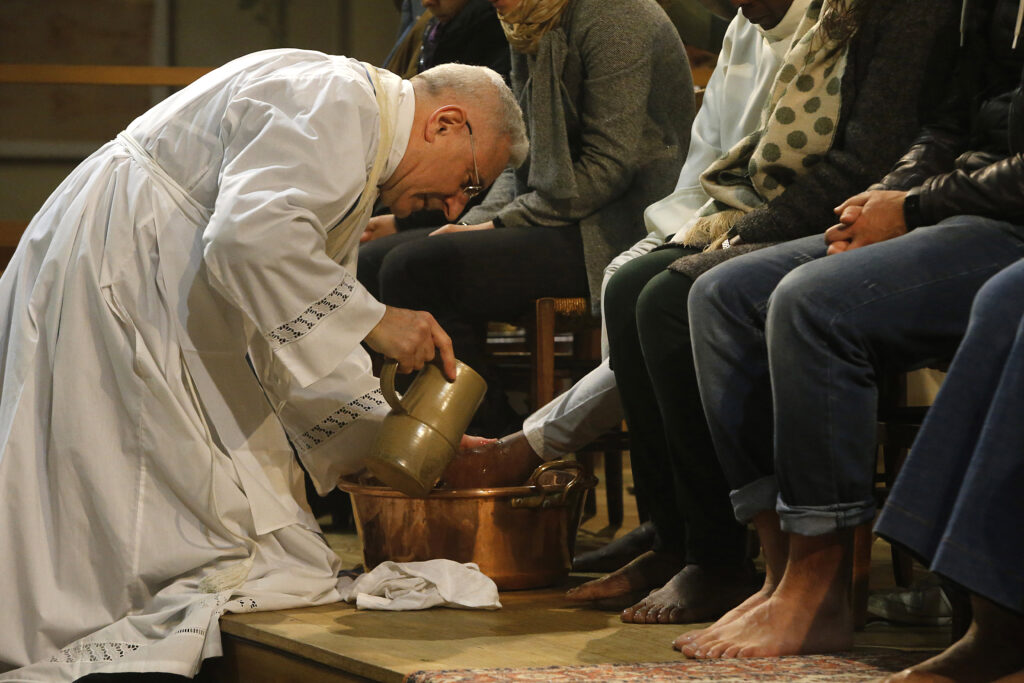

Liturgically we experience connection by giving and receiving touch in such rites as baptism, confirmation, healing, foot washing, and sharing the peace. In these acts of connection through mutual touch we move from the personal body to what Buddhist teacher of meditation Reginald A. Ray, PhD inTouching Enlightenment (Boulder, CO: Sounds True, 2008, 2014) called “the interpersonal body”. The interpersonal body is a deeper layer of the personal body. It can be awakened by connecting body-to-body with other humans but also other sentient beings.

Moreover, in connecting bodily with others we learn more about our own bodies. This is certainly the case in bodily connections between spouses who get to know each other’s bodily self intimately and experience the interpersonal body in their sexual relations. The perfect interpersonal body is created through coitus when “the two become one flesh.”

Touch is a social act. Our socially-formed sense of freedom or constraint in how we touch one another has liturgical consequences. Americans are not as free with interacting bodily with one another as people in other societies. For example, there is still resistance to sharing the greeting of peace with one another in the liturgical assembly by handshake or hug. In some assemblies the Maundy Thursday foot washing as a profound symbol of servanthood has been replaced with mutual hand washing. We have become touchy about touch. The widespread experiences of sexual abuse and harassment exacerbates this aversion to touch in our society. This has a negative impact on practicing healthy forms of mutual touch which we all need.

Bodily connections can be experienced in massage. I included some passages about massage in my book. Regular massage has therapeutic benefits. But massage is also a sensual experience. It can also be a spiritual experience. I suggested in that book that receiving massages in other societies, as I did in Singapore and Indonesia, also provides some clues to attitudes toward the body in other cultures. Massage deepens awareness of the personal body. But connection is also made between the masseur and the client through the application of the masseur’s hands and arms and, in Asian massages, sometimes knees and even the chest.

Given our current social context we need to ask whether the members of the assembly of faith in Christ Jesus, formed by the Holy Spirit through word and sacrament to be the body of Christ, are able to interact bodily with one another in ways that are not available in the society outside the assembly’s space. I address this critical issue in “Frank Answers About Connection and Touch.”

The Cosmological Body: Sex and Death

Within his five dimensions of the body Johnson did not discuss the meanings the body received from a cosmological or worldview perspective, particularly the role of sex and views of the afterlife. Is sex just the expression of inner needs lodged within an individual body or is it the energy of the universe pulsing through the body and not intended just for the isolated body alone? How do we live in our body here and now in the face of the body’s inevitable death? Sexuality and death are constants in human history since, biologically, sex is related to procreation. The death of the mother and/or the child in childbirth was a common occurrence before modern medicine. (A number of other species experience death after copulation [the male] or after laying eggs [the female].) In modern times, the AIDS epidemic added to the fateful relationship between sex and death. French social theorist Michel Foucault said that the death instinct pervades all sexual activity. In The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (New York: Vintage Books, 1978, 1990), p. 156, he referred to orgasms as “little deaths.” The Faustian pact is “to exchange all of life for sex itself.” (There is no entry on “sex” in Johnson’s index or a reference to the work of Michel Foucault in his bibliography. )

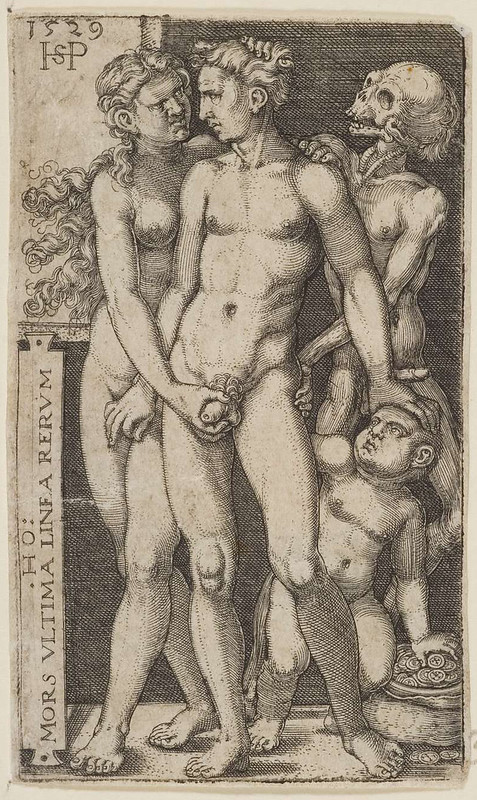

But sex and death are related cosmologically as well as biologically, which is why I treated marriage and funeral rites together in Chapter 7. Sex and death have been regarded as cosmic realities that transcend biology, environment, personal experience, social conventions, and cultural expressions. Marriage and funeral rites express respectively creation myths and eschatological hopes that are perhaps more related to a theology of the body than to philosophy. Below is the engraving “Death and the Indecent Pair” by Hans Sebald Beham (1529). The Latin inscription reminds these lovers that “Death is the end of all things.” How does that stark reality impact the vitality of bodily life as we live it in our present lives?

Gnostic Issues

There is, finally, the “so what?” question. What does this mean for us? It means that the body has a place of honor in Christianity. Elaine Pagels, the noted authority on ancient gnosticism, admits that “orthodox tradition implicitly affirms bodily experience as the central fact of human life. What one does physically — eating and drinking, engaging in sexual life or avoiding it, saving one’s life or giving it up, connecting with others through touch—are all vital elements in one’s religious development” (Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels [New York: Random House, 1979], 101). Gnostics of all ages, ancient or modern, have a profound distrust of the body and the material world. American religion, as Harold Bloom so perceptively saw, is pervasively gnostic. (Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation [New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992]). Gnostics distrust nature, history, institutions, sacraments, and the body itself and seek an escape from all of them.

Gnosticism is not a religion in itself but a cultural attitude. At the end of my book I called attention to the perennial temptation of Christians to succumb to the gnostic mindset. Gnostic spiritualism undermines salvation by rejecting the very sources of salvation—the incarnation of the Word in human flesh, the death of the Son of God on the cross, and his triumph over death in resurrection of the body. Resurrection itself implies that the material world, and the human body itself, is salvageable in a new creation. The resurrected body will be a glorified body, but nevertheless a body, such as we see in the resurrection stories of the risen Jesus. Below The risen Christ greets Mary Magdalene in this painting by Fra Angelico, Florence, 1440.

My project of promoting embodied liturgy is intrinsically anti-gnostic because ritual by its very nature uses material things, engages human bodies in the use of these things, and is dependent on times and occasions and routines. Sacramental rituals like Baptism and Holy Communion use material elements like water and oil, bread and wine as means of grace by which God connects with us bodily. In my recent book, Eucharistic Body, I reflect on what it means that we receive into our bodies (and biochemistry) bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ. In the reception of the sacraments we are one with Christ physically as well as spiritually. Our repertoire of rituals sanctify bodily life in our waking and sleeping, eating and drinking, fasting and feasting, having sex and abstaining, healing the body when it is sick, and imbuing it with dignity when it is dead.

In a sense this has been the project of my life as a liturgist. In my yoga practice I go ever deeper into my own body and in embodied liturgy I employ my senses and motor actions to connect more deeply with God, with others, and with the world of which I am a part. I appeal to the philosophy in the flesh and the theology of the body as the basis of embodied liturgy. Continuing in this journey I expect to explore further the dynamics of bodily movement—the movement of God toward humanity in word and sacrament, movement that engages us with our surrounding environment, and the movement of bodies in the assembly forming a corporate body. To call the liturgical assembly “the body of Christ” is not just a metaphorical description; it is actual bodies brought into union with Christ in the sacraments, present to the Lord and to one another in the assembly, and sent into the world at the dismissal.

I have summed up in this article the thought and work of my recent years and indicated where I am moving in my present and future projects. A massive “return to the body” has been taking place in philosophy, neuroscience, psychology, and the arts in the last several decades. Hopefully theology and liturgy will catch up. We can no longer do liturgical history, liturgical theology, or liturgical praxis without recognizing the most basic fact about liturgy: it involves the bodies of worshipers, bodies that are biological entities, environmentally situated, phenomenologically experienced, socially conditioned, and culturally expressive.

Pastor Frank

Frank Senn

I’m a retired Lutheran pastor. I was in parish ministry for forty years and taught at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago for three years. I’ve been an adjunct professor at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, IL. Since my retirement in 2013 I’ve also taught courses at Trinity Theological College in Singapore, Satya Wacana Christian University in Salatiga, Central Java, Indonesia, and Carey Theological College in Vancouver. I have a Ph.D. in theology (liturgical studies) from the University of Notre Dame.

Read Next →

© 2022 Frank Answers

Theme by Anders Norén